Introduction

Each intern brought their background in landscape architecture, historic preservation, and history to this project. What follows is an abbreviated version of their 30-page report focusing on examples from each era that was examined. The interns also presented their findings to Town Council.

Credit: Joanna Luchese, Isa Lewis, and Anthony Mendez

Pioneer Era

Pioneer Era: 1860-1900

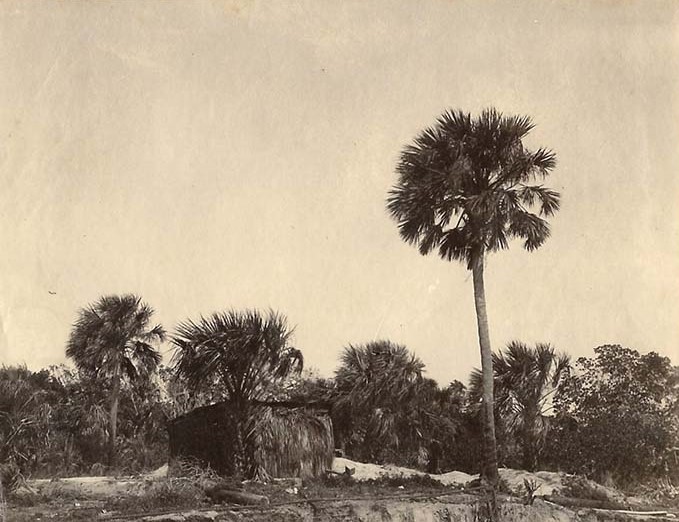

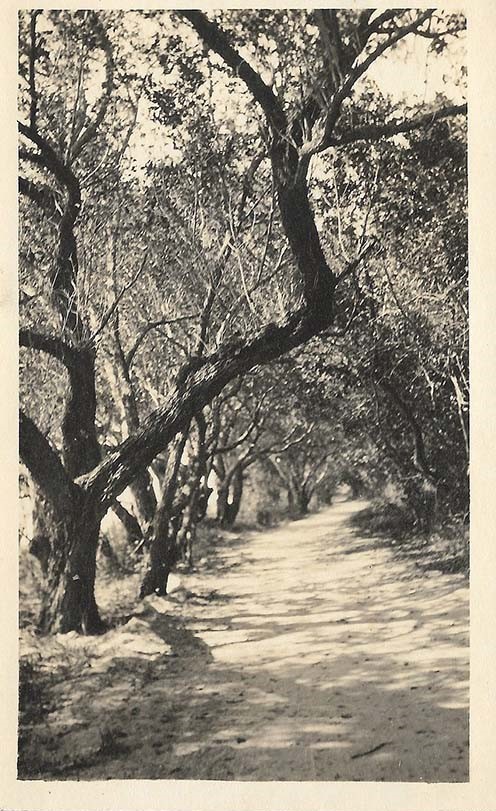

When the Spanish arrived in Florida in 1513, the southeastern fringes of the state were occupied by the Tequesta and Jaega tribes. After years of disease and oppression, these Native American tribes were not able to survive; they are now commonly referred to as the “Lost Tribes” of Florida. Later, throughout the 1800s, groups of Creek Native Americans from Alabama and Georgia were pushed past northern Florida and into the Everglades during three Seminole Wars. After the Homestead Act of 1872 white settlers began occupying the barrier island of Palm Beach, which was considered to be not much more than remote “jungle” wilderness at the time. However, they carved self-sustaining communities out of a dense mass of marshy swamps, sandy dunes, and forests thick with oak and pine. Most of the homesteaders came to South Florida in order to farm or make the most of what was available—not to cultivate a particular image of paradise—that would evolve decades later.

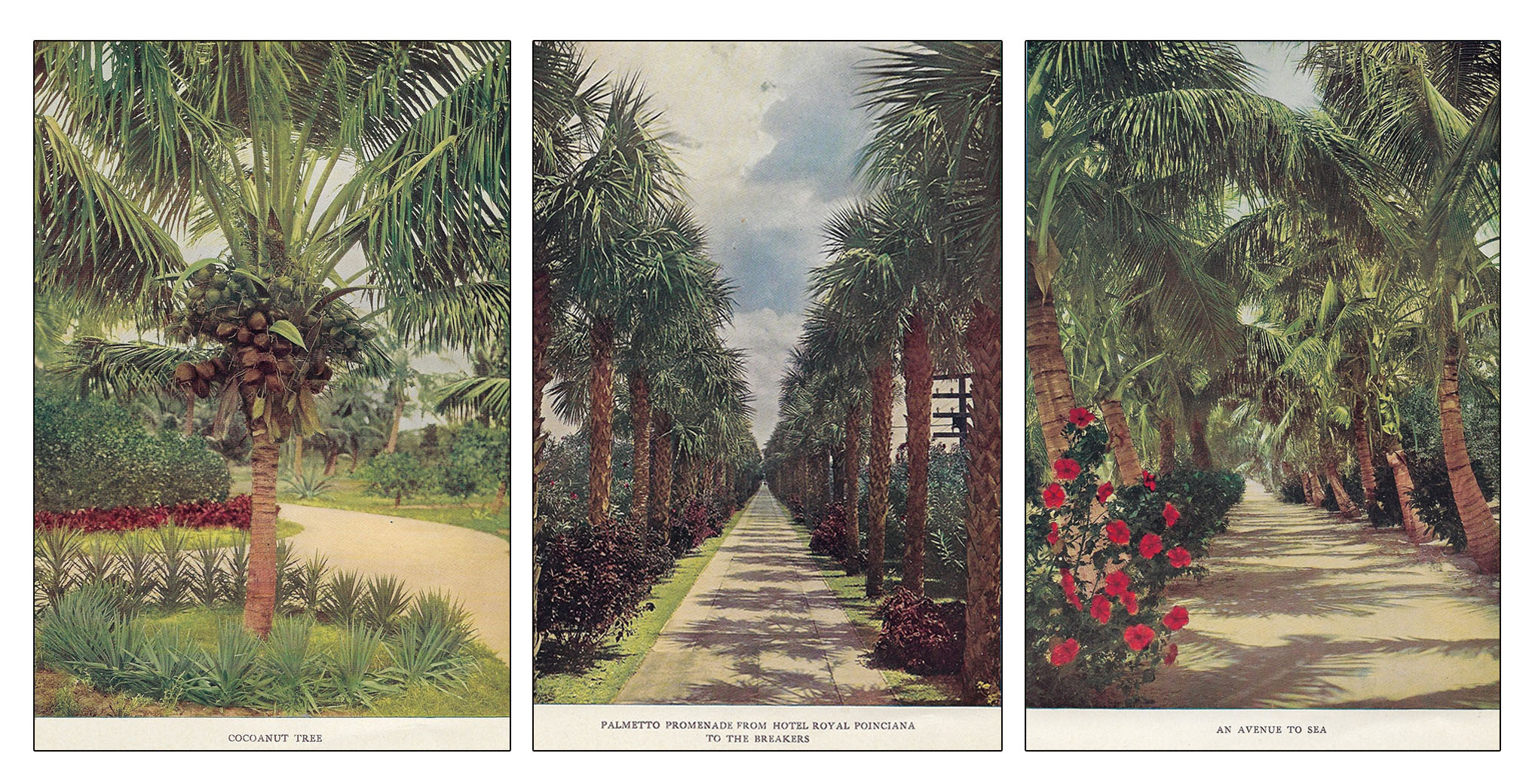

Starting in the 1890s, it was ultimately because of people like Henry Flagler that Palm Beach was transformed into a seasonal destination; the development of this destination, however, came at a steep price. Attractions like the Garden of Eden suggest that the early winter residents of Palm Beach were interested in a cultivated image of “natural” Florida which would sometimes mimic rather than truthfully represent its native ecology.

Boom & Bust

Boom & Bust: 1900-1929

Throughout the 1920s, Palm Beach homeowners began to flock to the island as seasonal winter residents and showcased their ostentatious wealth through the construction of grand, palatial estates, often built to mimic the older architectural styles of Europe and designed with an imposed image of tropical paradise in mind. Scores of tropical plants were integrated into the landscape designs of these estates and many homeowners chose to plant tropical vegetation among or alongside existing native growth.

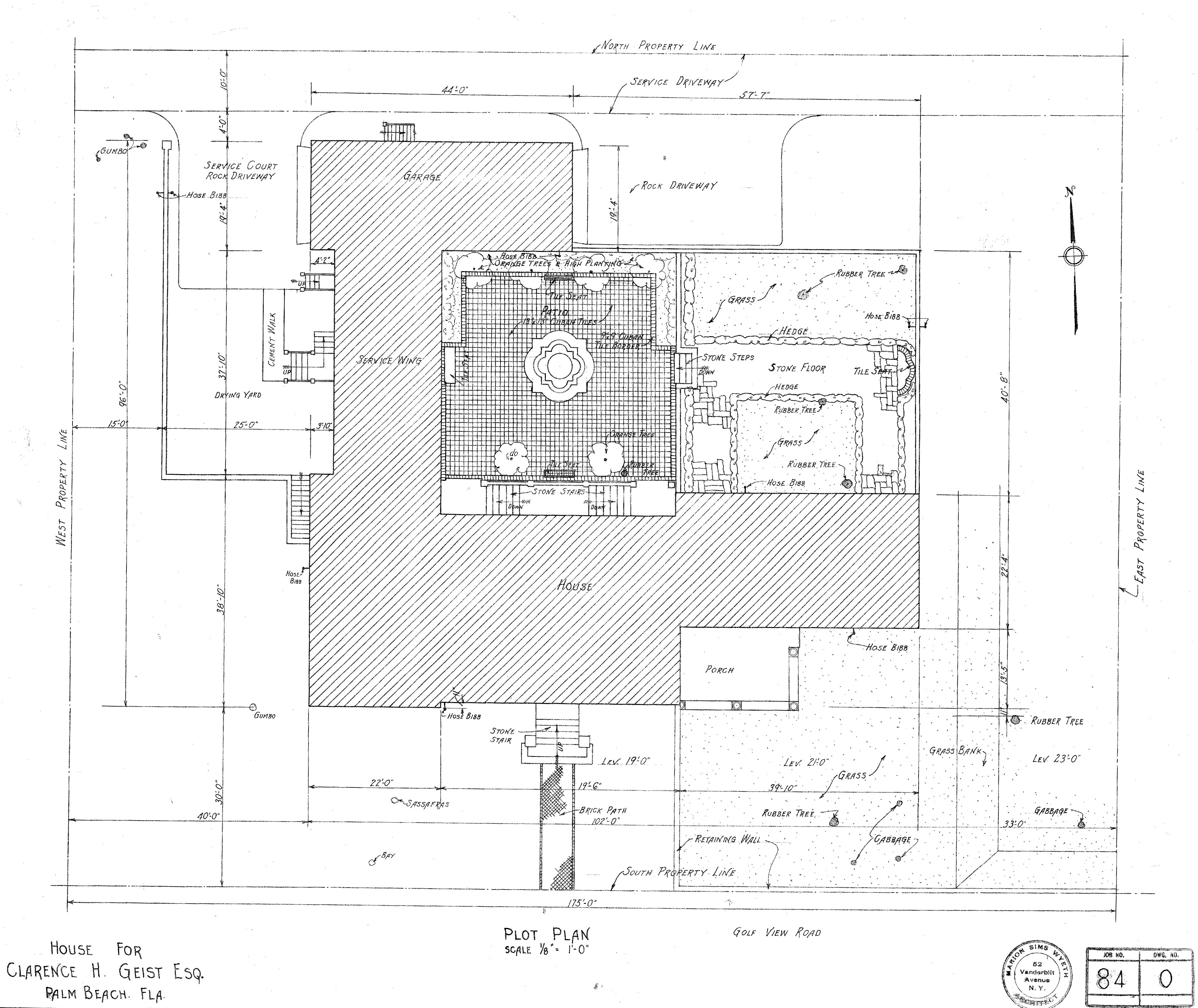

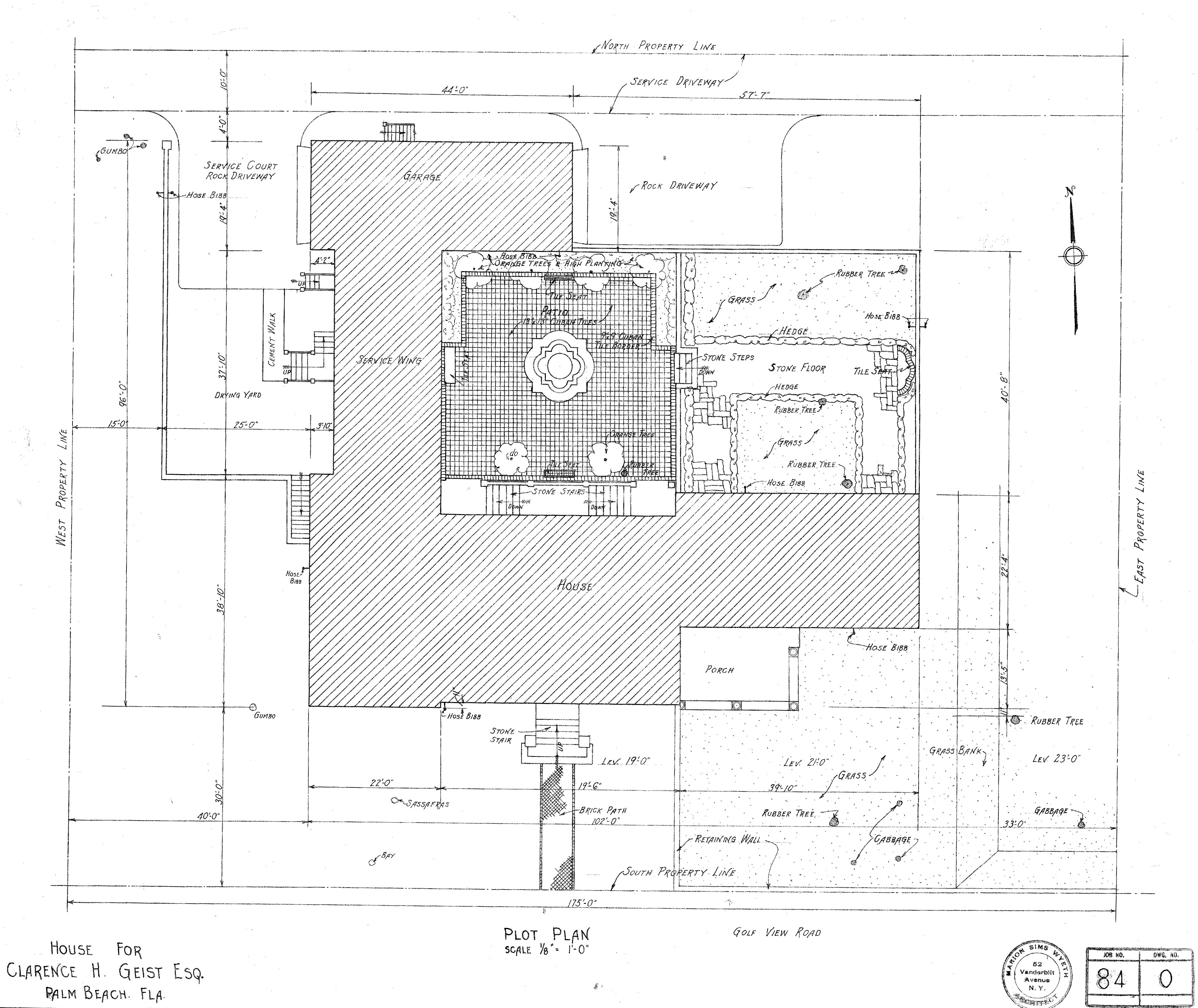

Hogarcito, a Spanish Mission style estate designed by Marion Sims Wyeth in 1923, featured a blend of seemingly preserved but pruned native growth and a more ornamental cloister-style garden. The mix of native and exotic plants in the raised beds make Hogarcito a remarkable example of how non-native plants were stylistically integrated into existing native growth during the 1920s.

For the full delight of residence here is not to be had unless the dwelling comports with the climate and the scenery. It is a waste of good material indeed, if good solid materials and the craftsmanship of artisans are not to be manipulated and blended to produce, as they can produce, a structure that chimes with the harmonies of nature.

1922

Marion Sims Wyeth designed Casa Alejandro, a Mediterranean Revival style residence for George McKinlock, whose wife Marion, was the first president of the Garden Club, in 1924. It featured an Italian-style garden designed by William Lyman Phillips. Phillips worked for the Olmsted brothers for twenty-two years before arriving in Florida. Once of his best-known landscapes is the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables.

The latest expression of the taste in houses and gardens of a people who dare everything, who spare nothing to create what they desire—this is Palm Beach in its present phase.

Landscape Architecture, 1924

Redefining Space

Redefining Space: 1930s

The 1929 Plan of Palm Beach, prepared by the Garden Club of Palm Beach and approved by the Town Council, provides insight into how the Town made plans for its increasing population and businesses. The Plan correlated with the City Beautiful movement — one of the most important movements in American landscape architecture — it promoted the construction of public parks for improved public health and prestige. The Palm Beach Plan featured beautified streetscapes, a public bathhouse, and a botanical garden.

Overall, Palm Beach landscapes in the 1930s were distinctly formal and ornamental in design, often showcasing tropical or rare plants which could not be grown anywhere else in the United States. As opposed to the 1920s, the objective of many landscape designs throughout Palm Beach in the 1930s seems to have been one of experimentation and cultivation, and often for the purpose of greater public enjoyment.

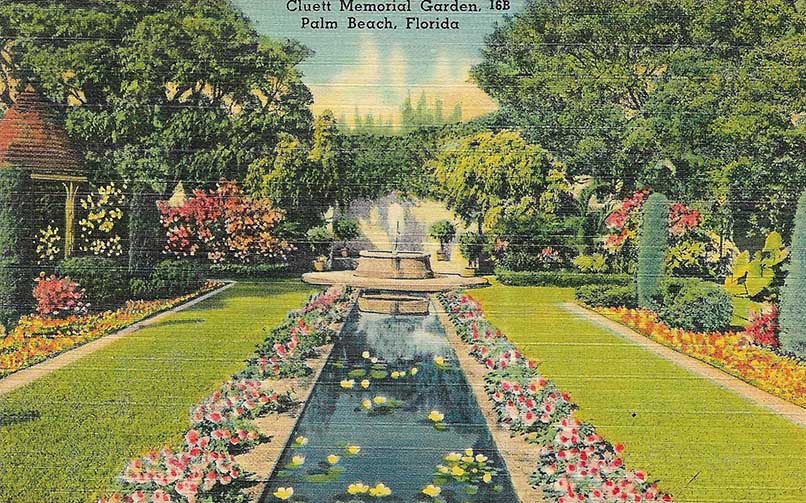

Dedicated in 1929, the Memorial Fountain, designed by Addison Mizner, was surrounded by a formal public garden. It was designed by Charles Perrochet, a landscape architect who also worked for the Island Landscape Company and was a member of the Art Jury—which formed as a local commission in 1929 to approve building designs.

Nowhere in Palm Beach are there such extensive gardens.

Mid-Century Shift

Mid-Century Shift: 1940s and Beyond

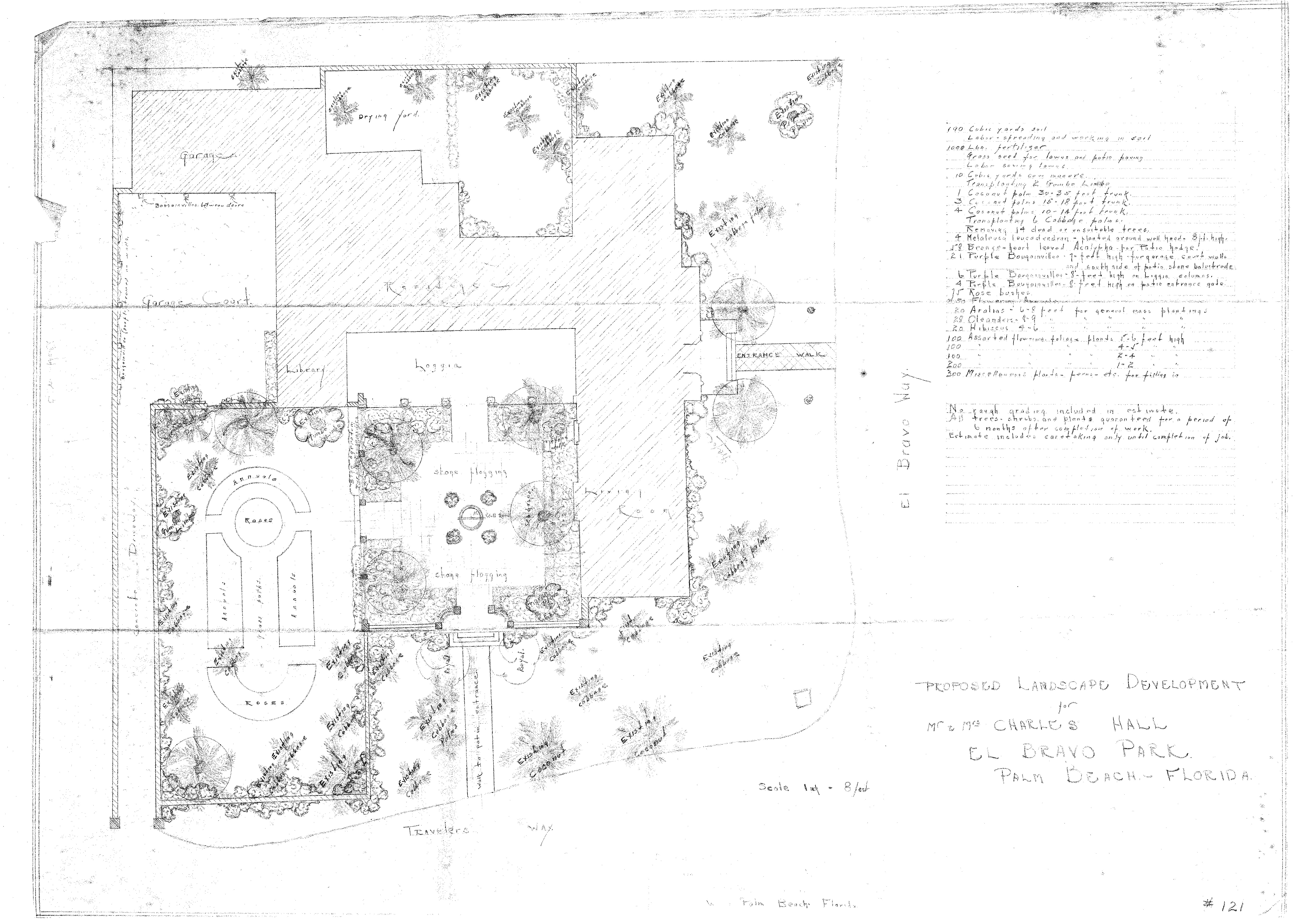

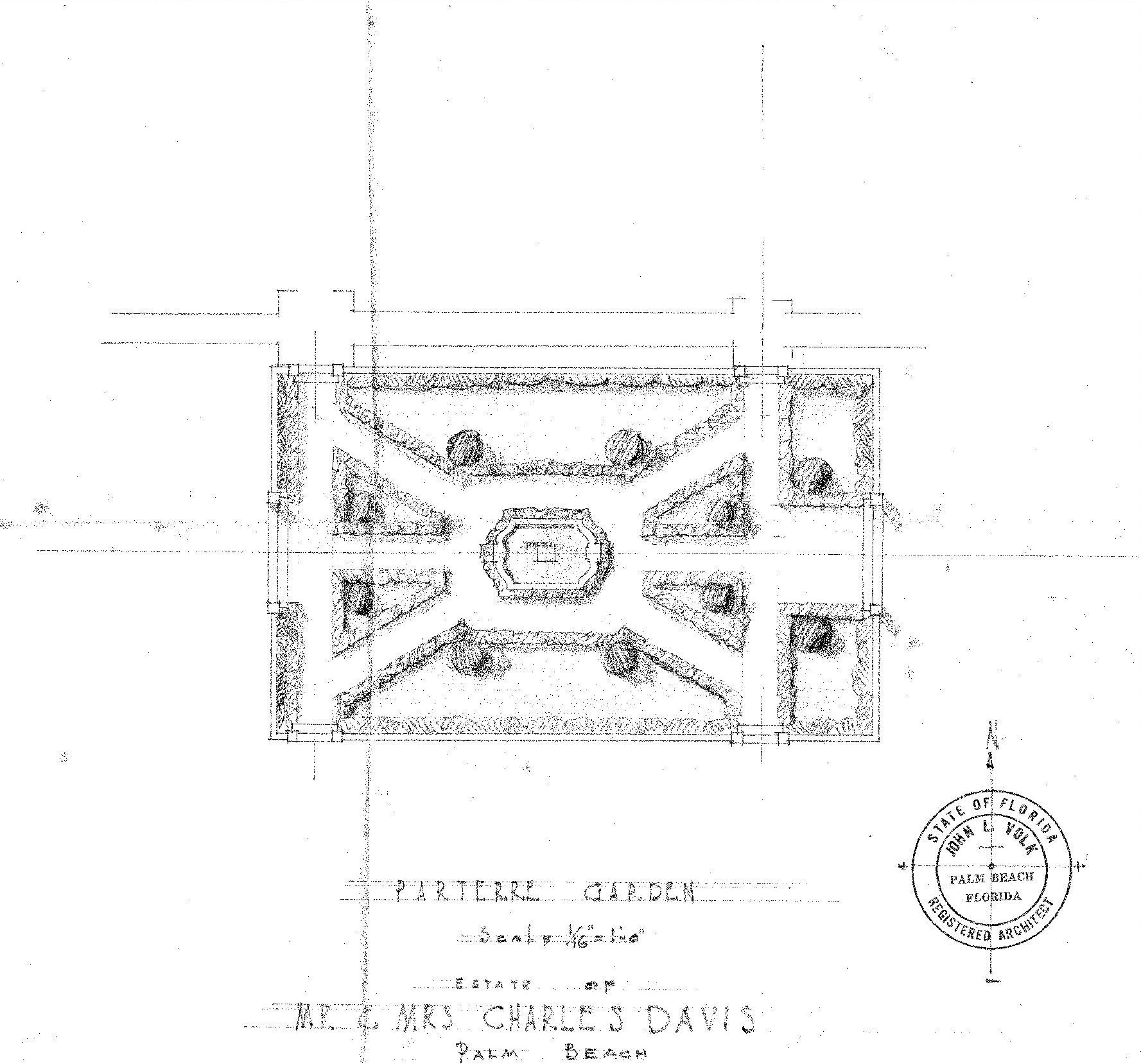

Landscape architecture trends began to subtly shift after the World War II. Beginning in the 1940s, Palm Beach saw the intentional incorporation of native plants into landscape designs, signaling a growing understanding of the inherent value of ecology. The formality so deeply engrained in the landscape architecture of the 1930s began to loosen. Intentional integration of native plants seems far more prevalent in the 1940s and 1950s. Overall, landscape design in Palm Beach became more generalized to fit the changing architectural styles of this era, which were often more modern and simplified. Plants like bougainvillea went out of fashion as less Mediterranean style homes were built.

The Boynton Landscape Company was founded in 1919 by James D. Sturrock, the firm had been working for over twenty years before architect John Volk began to rely on their services for his commissions. In Palm Beach, the Boynton Landscape Company was evidently at the forefront of landscape design; they would soon come to be known for a diverse range of projects. George Sturrock, President of the Boynton Landscape Company stated that post World War II, creative work was on the decline and that color was more in demand.

Landscaping has to do with translating a client’s ideas to a garden that reflects his personality.

president of the Boynton Landscape Company, 1967

Conclusion

Conclusion

This project has been the Preservation Foundation’s first foray into the history of landscape architecture in Palm Beach, and we hope it inspires more research on the subject. In working on this report, we discovered that Palm Beach residents have been using non-native plants to cultivate the town into a tropical paradise for more than a hundred years. However, we also found that they have been leaving existing growth untouched or intentionally incorporating it into landscape designs for just as long. Many historic residences, including the ones featured in this report, seem to have met or even exceeded the current 35% native benchmark long before it was put in place. The town in general was not always as manicured as it is now, and the aesthetic appeal of non-native materials has always been enhanced by the preservation or incorporation of native plants. In light of this, we hope to set historic precedence for the use of plants which support the ecological health of Palm Beach in new landscape development. The value of native plants is only just beginning to be fully realized in Palm Beach, where natives have consistently been used as a legitimate element of the island’s beauty, health, and character.

I’ve always felt that the architecture came first and the landscaping had to follow. We have to get away from today’s tendency to fill every space with great masses of flowers, bushes, and shrubs.

landscape architect for the Boynton Landscape Company, 2003