Introduction

In a time as contentious as ours, it is crucial to acknowledge and honor the contributions and legacy of minority pioneers. In this vein, the Preservation Foundation has chosen to highlight a significant historically Black community that existed on Palm Beach, known as the Styx. From its creation as a housing project for workers involved in the construction of Henry Flagler’s hotels, the Royal Poinciana and the Breakers, to its eventual end, the Styx became a center for the African American community in the area. Over time, it has been almost entirely erased from public memory. This exhibit’s goal is to reconcile the oral history legacy of the Styx with that of the documentary history and shine a light on the circumstances that led to its demise.

Serving as the legal basis for the creation of this community were the infamous Jim Crow laws. This set of legal and social codes dictated almost every aspect of life in the post-Civil War era in the United States.

Origins of The Styx

Origins of The Styx

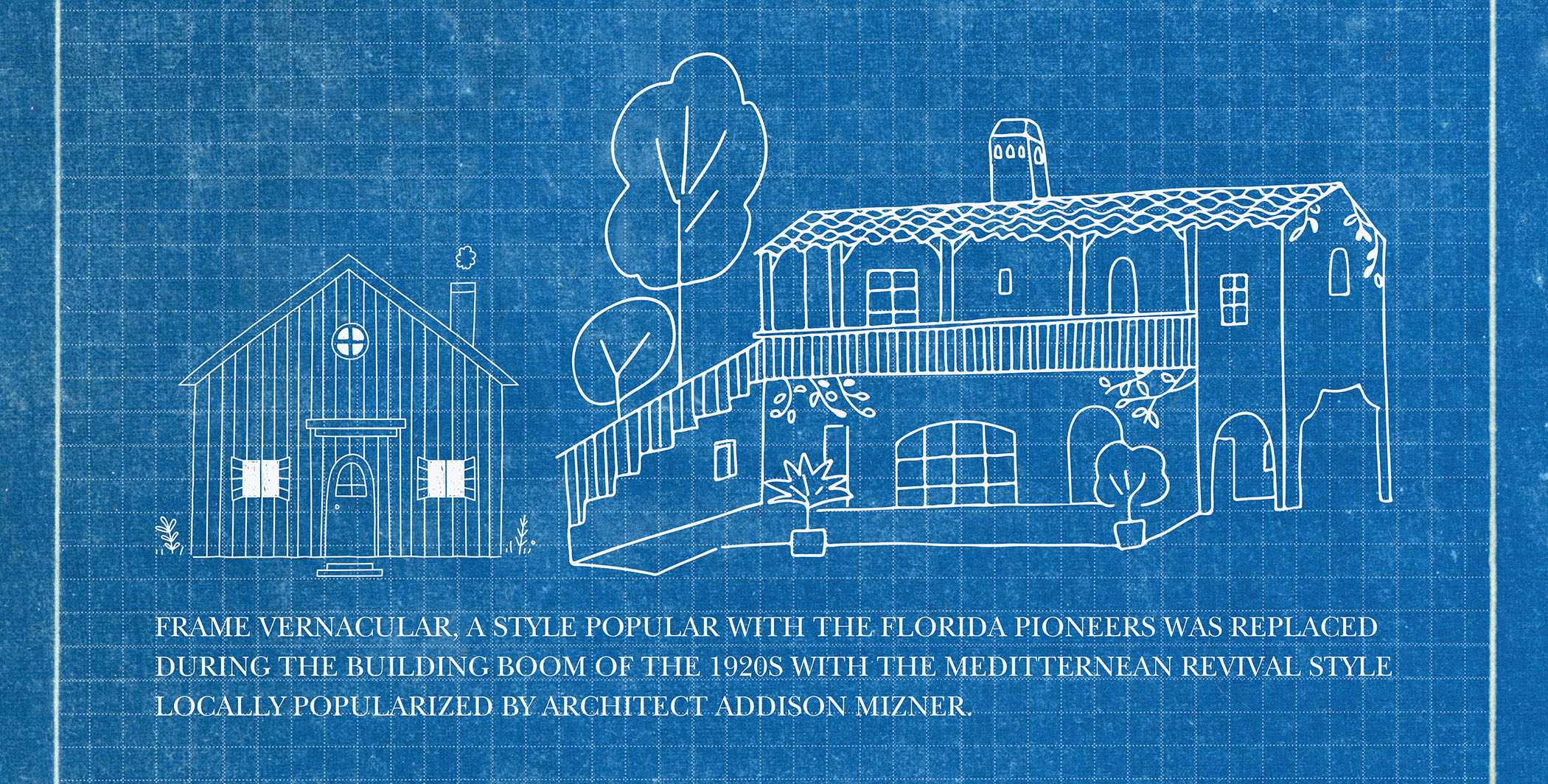

Built to be a retreat for the wealthy, Palm Beach’s built environment exists as the result of thousands of African Americans who traveled from different regions of the United States and the British Caribbean to develop the area. In the 1890s, advertisements and word-of-mouth brought African Americans to Palm Beach via ferry with the promise of work building the East Coast Railway and both of Flagler’s hotels, The Royal Poinciana and The Breakers. These underrepresented pioneers continued to work in Flagler’s hotels during the season, initially lasting from New Year’s Day to President’s Day, as well as in the off-season, working for wealthy families living on Palm Beach.

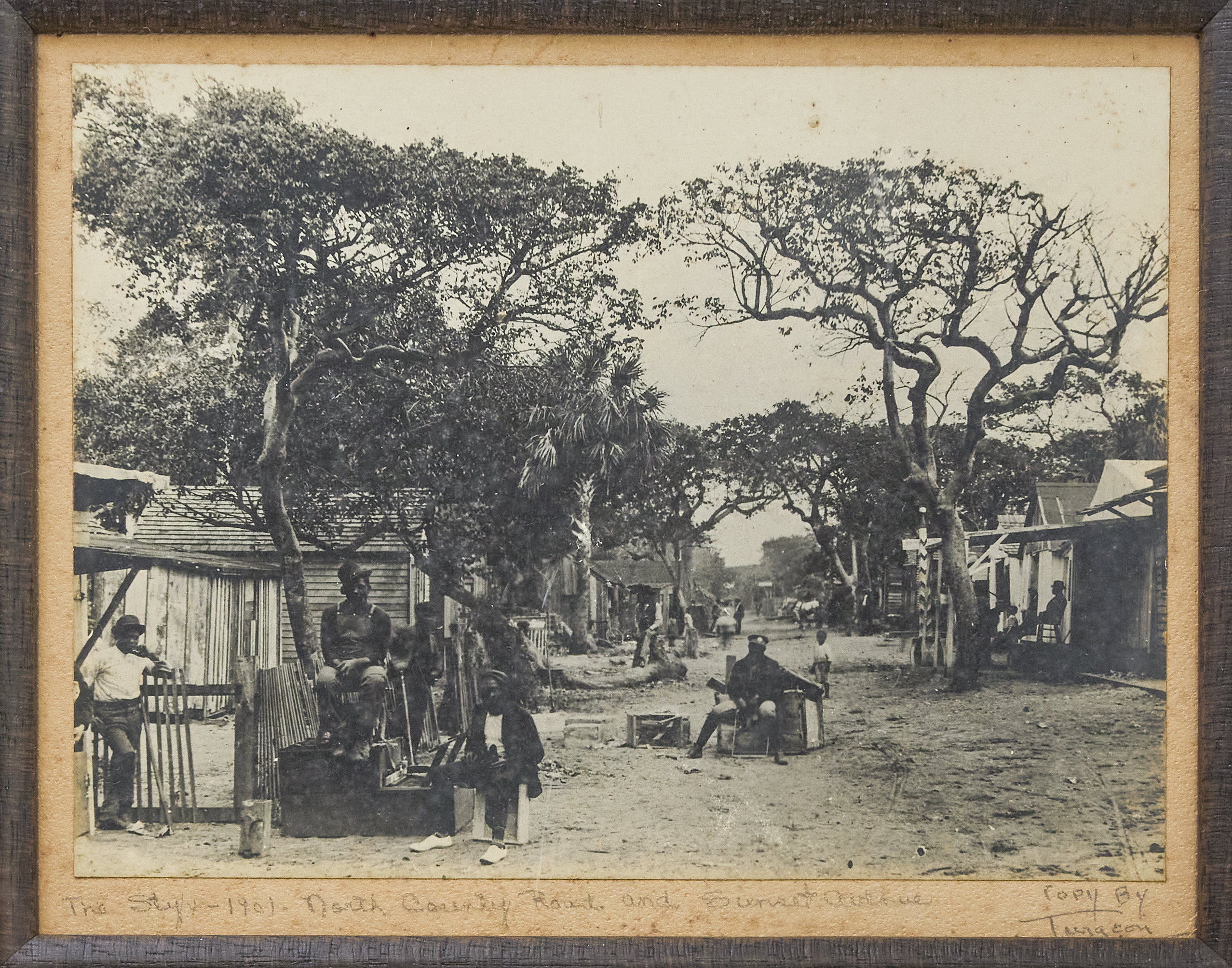

However, as development rapidly increased on the island, these workers were compelled to live in an area coined by the elite as “The Styx,” which was located on Sunset Avenue and County Road. Its name refers to the River Styx in Greek mythology, which led into the underworld and is described as being the color black. At a time when Jim Crow laws were at their peak, hotel moguls preserved racial separation on the island with the creation of a Blacks-Only community.

Creating Community in the Styx

Creating Community in the Styx

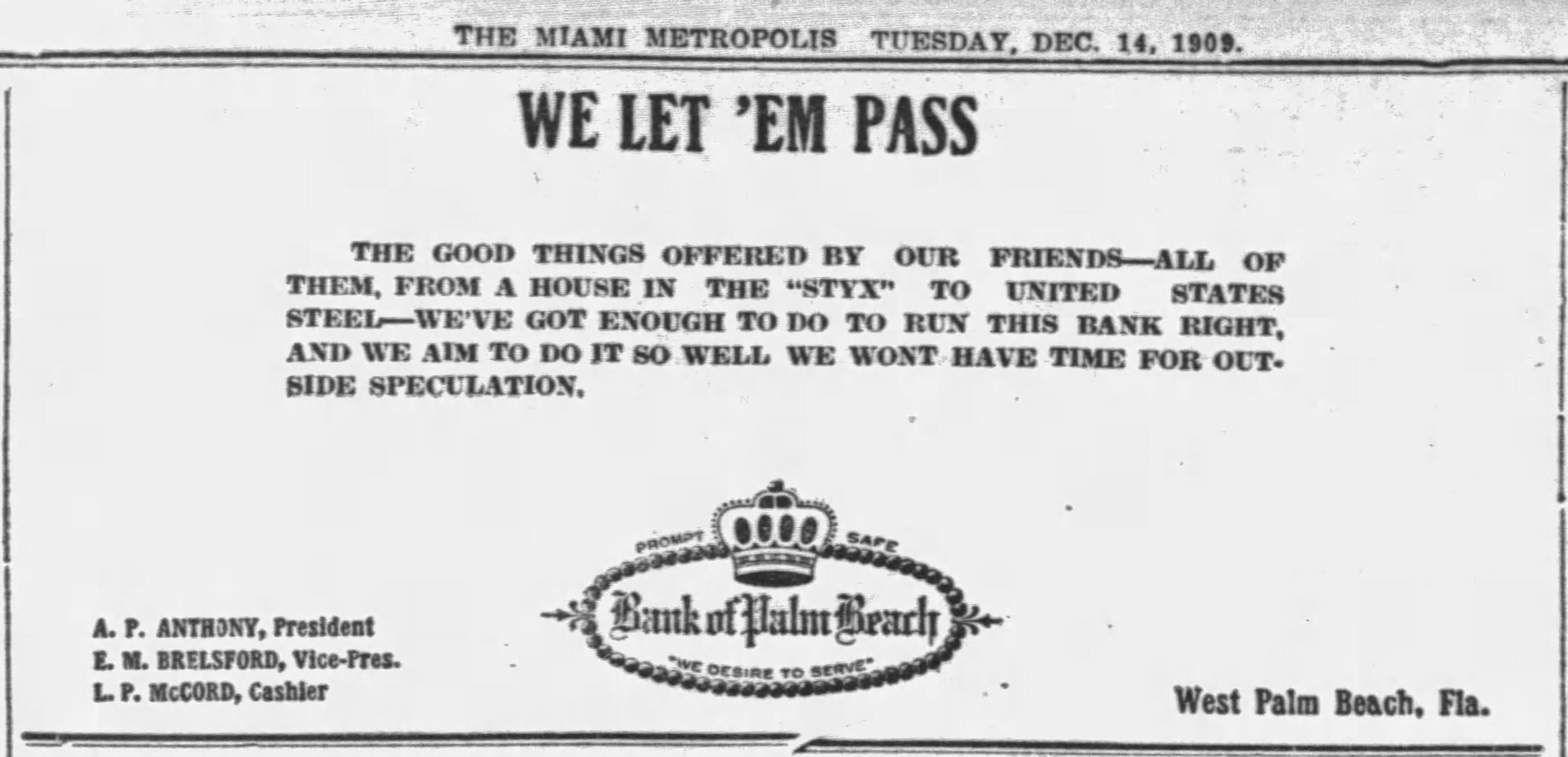

The Styx was a shanty town with quickly-made wooden structures that, at its peak, housed almost 2,000 African Americans. The Styx community was built on land owned by pioneers Henry Maddock, E.M. Brelsford, and Dr. James M. Munyon. Tenants paid $3 a month which was typically collected by designated resident Thomas T. Peppers. In addition to residences, it also consisted of multiple churches, storefronts, and a dance hall. Inez Peppers Lovett, who spent her early life in the Styx, described the experience to the Palm Beach Post: “We had school at the St. Paul A.M.E. Church in the Styx, and we had birthday parties and picnics at the ocean. A woman and her husband had a dance hall in the Styx for adults. A man nicknamed ‘Rabbit’ played rag-time music on the piano.”

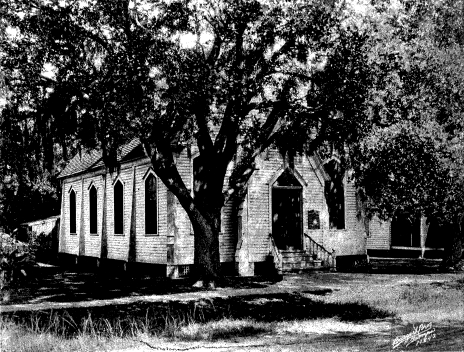

This was not the only occasion where religion played a role in this community. Both Payne’s Chapel AME Church and Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church were founded in 1893. Seeing the need for religious organization, the churches’ founders began hosting weekly meetings and erected both churches in the Styx. Churches quickly became the heart of the community, and eventually moved their spaces to West Palm Beach as they outgrew their Styx facilities. The churches became the base for the new African American community in the now Historic Northwest.

Work & Entertainment

Work & Entertainment

Leisure activities were a major part of the White experience on Palm Beach during the era. As a result, African American workers were expected to create a pleasurable environment. Some of these experiences included Afromobile services between the resorts and Baseball games staged between members of the staff.

Afromobiles

A popular tourist vehicle for hotel guests to explore the various jungle trails were wicker chairs attached to bicycles. A key reason to its popularity was that the vehicle was an open air structure that was perfect for the South Florida climate. Known as wheelchairs, they were commonly driven by Black hotel workers. Due to their drivers’ descent, these wheelchairs became commonly known as Afromobiles, reinforcing the racial divide. They continued to be a part of Palm Beach leisure until they were phased out in the mid-twentieth century and replaced by cars.

The Hotel League

Already established as “America’s Pastime,” baseball became a mainstay of the resort season on Palm Beach. Made up of waiters, bellhops, dishwashers, and other employees hired specifically for their skills as baseball players, the Hotel League served as a major entertainment source for visitors between January and March from the early 1900s through the 1920s. Twice a week, these employees would don uniforms bearing either “Breakers” or “RP” for Royal Poinciana and compete for the entertainment of hotel guests. Based on an oral history by Palm Beacher, Frank Quigly, “—whoever hit the first home run, when the colored guys played their game, Stotesbury would give him a $10 bill” making the game lucrative for all those involved. The League would serve as a precursor to the “Negro League.” Former Hotel League players included CI Taylor, who would serve as a founder and team owner in the Negro League, and Ashby Dunbar, an outfielder who played for several Negro League teams.

The Eviction

The Eviction

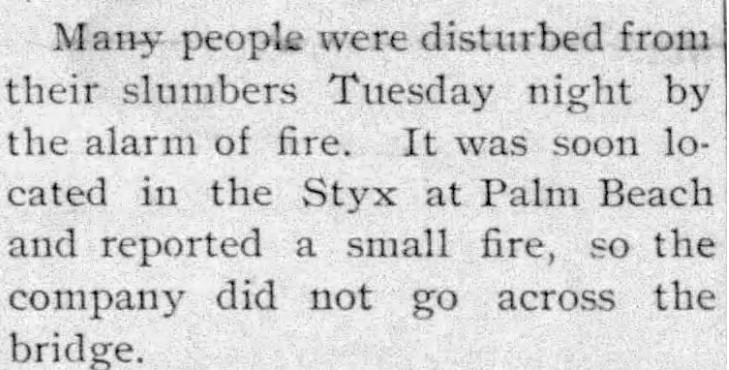

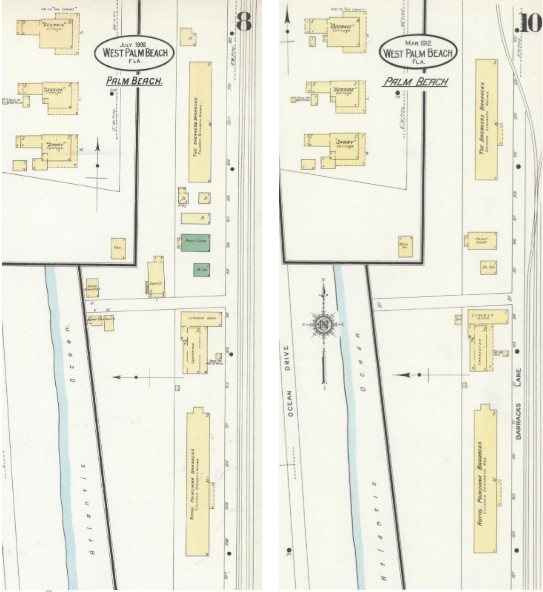

As early as the spring of 1903, the deteriorating conditions within the Styx became impossible to ignore. Built without running water or sewer access, sanitation became a significant problem. Other risks included fires as most structures were hastily constructed from wood. Additionally, while many residents paid rent to their landlords, newslines increasingly noted the instances of squatters and criminal activity. As a result of the terrible conditions, there were calls from the community to investigate and “clean up” the area. Seeing this as a great opportunity, the landowners began selling to redevelop the area.

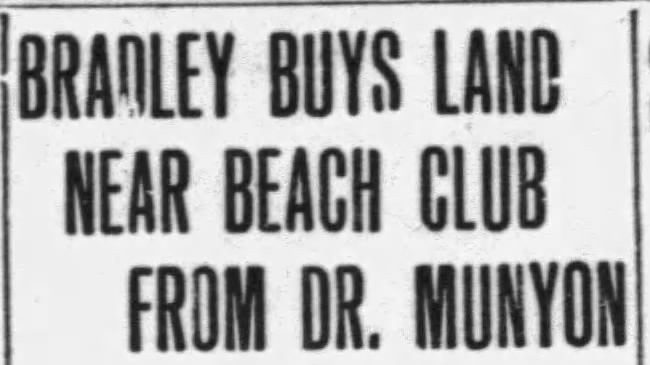

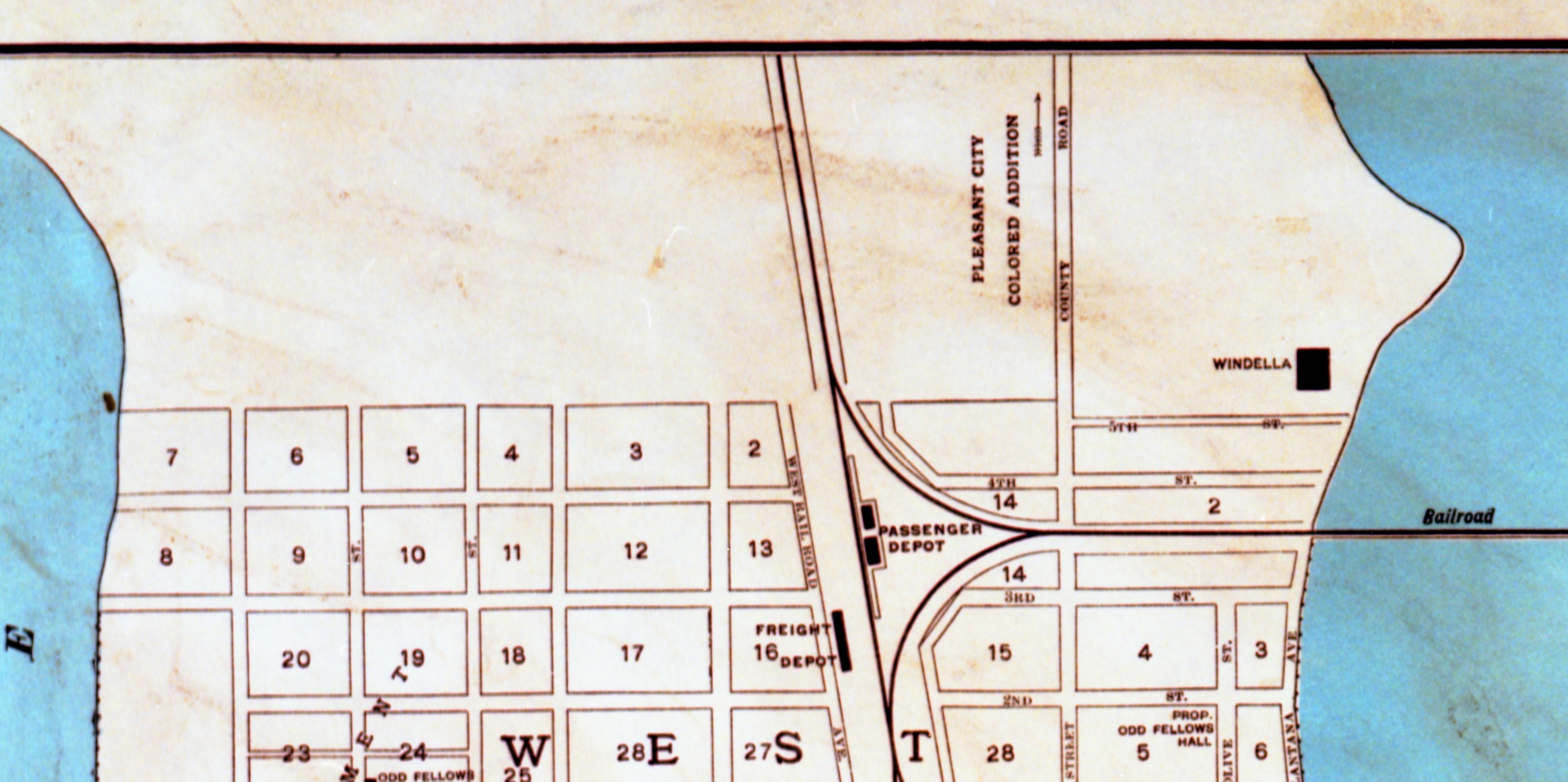

By 1904, plans were made by owners such as Dr. James M. Munyon to tear down the Styx and replace it with an expansion of the Bradley Beach Club and cottages, which were to be rented to white tenants. The plans were finalized in 1910, transferring the ownership of the land from Munyon to E.R Bradley. The African American inhabitants of the Styx were relocated to the newly minted Pleasant City community in West Palm Beach. For as little as $150, about $3,600 today, African Americans could buy a plot of land in Pleasant City from the Currie Investment and Title Guaranty Company, owned by land developer and one-time West Palm Beach mayor, George Currie.

The Styx community was formally disbanded in 1912, when the remaining residents were given two weeks to relocate. Once everyone had vacated, hired gardeners cleared the land and demolished what was left of the Styx. While historical sources state this was what happened to the Styx, an urban legend emerged that told a different account of the Styx’s removal. According to this myth, Flagler had invited those in the Styx community to celebrate Guy Fawkes Day, a British holiday, and as the workers participated in the festivities, their houses were burned down. While this longstanding oral tradtion has been debunked, it contributes to a holistic view of this community’s downfall.

Honoring Heritage

Honoring Heritage

Even though the Styx community was moved to both Pleasant City and the Historic Northwest in West Palm Beach, community members continue to acknowledge the role of the Styx in bringing their families to Palm Beach County. As a tribute to the Styx community, this August, the Historic Northwest, in partnership with the city of West Palm Beach, is hosting the grand opening of the Styx Promenade, including the display of nine Shotgun-style homes and six minority-owned businesses. This is one of the many ways the community is memorializing the Styx and its historical contribution to economic growth in Palm Beach.

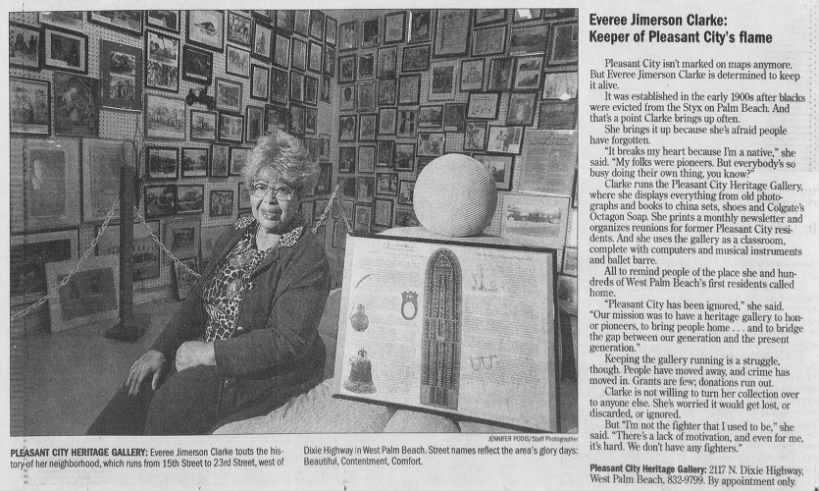

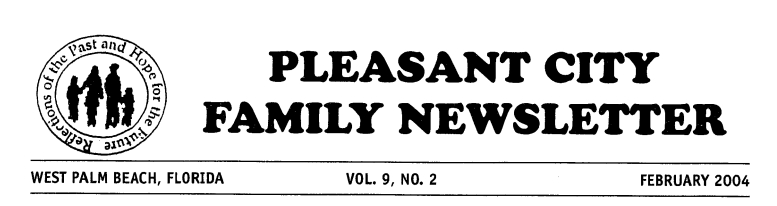

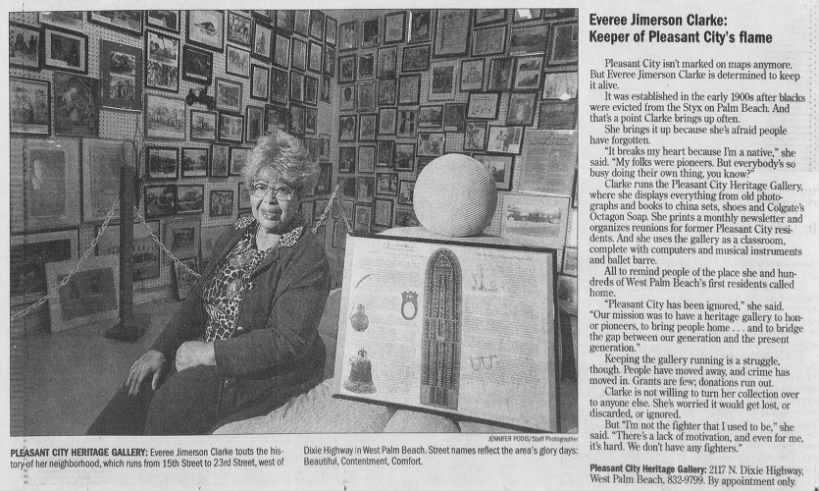

When the Styx was forcibly relocated to Pleasant City, many of the pioneers and their history were silenced until now. Their descendants have taken control of the narrative, founding the African American Research Library and Cultural Center of Palm Beach County, Inc., to open access to educational material on the history of the African American community. Additionally, before passing in 2022, Everee Jimerson Clarke, a Pleasant City and Black historian, authored Pleasant City, West Palm Beach, and founded the Pleasant City Heritage Family Reunion Committee and Gallery to recognize the community’s origins and its pioneer families. Visitors of the Black Archives in Miami can also request to view Clarke’s collection.

In spite of these efforts, there has never been a true resurgence of a Black community on Palm Beach. Historically, private clubs, such as The Everglades Club and the Bath and Tennis did not allow Black members. As of 2020, only 48 residents of Palm Beach reported being of African American descent. Although short-lived, the Styx had a lasting impact on the community, along with a rich history that is being shared. With this exhibit, we at the Foundation hope viewers understand and appreciate the contributions of these Black pioneers to the development of Palm Beach as we know it.

References

References

Books:

Braden, Susan R. The Architecture of Leisure: The Florida Hotels of Henry Flagler and Henry Plant. University Press of Florida, 2002.

Clarke, Everee Jimerson. Pleasant City, West Palm Beach. Arcadia Publishing, 2005.

Catherine M. Lewis, and J. Richard Lewis. Jim Crow America. University of Arkansas Press, 2009. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1ffjm30.5.

Roberts, Diane. Dream State. University Press of Florida, 2004.

Tuckwood, Jan and Eliot Kleinberg. Pioneers in Paradise. 2004 Edition. Longstreet Press, Inc., 2004.

Websites:

Cloutier, M.M. “The Men of Palm Beach Baseball: All-Black Hotel Teams of the Early 1900s.” Palm Beach Daily News, February 21, 2025. https://www.palmbeachdailynews.com/story/news/history/2025/02/21/palm-beach-baseball-all-black-hotel-teams-of-the-early-1900s/79206538007/.

Henry, Daja E. “How Mississippi’s Jim Crow Laws Still Haunt Black Voters Today.” The Marshall Project, April 4, 2024. https://www.themarshallproject.org/2024/04/04/mississippi-voting-rights-history-disenfranchisement?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=20672762571&gbraid=0AAAAADF7VuozkDxJuI-AYWJvKTe241864&gclid=CjwKCAjwvO7CBhAqEiwA9q2YJdxs0Q7p_2bATBWGrF4f9pY13C5WCoLLXEGuxDXgdMGFrV-LpRy9HhoCxOgQAvD_BwE.

“Learn About Our Rich History,” Historic Northwest. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://historicnorthwest.org/history.

“Our History: From 1893-2022,” Payne Chapel AME Church. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://www.paynechapelame.com/about-us.

“Pleasant City Family Reunion Committee Inc. and Heritage Gallery,” Pleasant City. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://pleasantcity.org/.

“Tabernacle History,” Historic Tabernacle Baptist Church. Accessed June 13, 2025. https://tabernaclewpb.org/tabernacle-history/.

“The Black Archives,” https://www.bahlt.org/.

Newspapers:

“A Killing at the Styx.” The Miami Evening Record, January 16, 1904. https://www.newspapers.com/image/615647410/?clipping_id=174157566&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjYxNTY0NzQx MCwiaWF0IjoxNzQ5ODI5NTAyLCJleHAiOjE3NDk5MTU5MDJ9.DtASifCRwr3Ys2RnN1vz5yEojt8QFnpl1kdb8ml1q-I.

“Bradley Buys Land Near Beach Club From Dr. Munyon .” The Daily Metropolis. March 22, 1910. https://www.newspapers.com/image/297512525/?fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI5NzUxMjUyNSwiaWF0IjoxNzQ5ODI4 NjQxLCJleHAiOjE3NDk5MTUwNDF9.lp2qdp7n93L4K1SgQdsyBwWe8_p_GeogJLgBWZsG7VU.

Currie Investment and Title Guaranty Company. “Currie Investment and Title Guaranty Company.” The Tropical Sun. West Palm Beach, November 13, 1913. https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00075915/00651/zoom/0.

“Daily Doings: West Palm Beach Is Experiencing Summer Quiet.” The Miami Evening Record, August 25, 1904. https://www.newspapers.com/image/615648870/?fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjYx NTY0ODg3MCwiaWF0IjoxNzQ5ODI4MjI2LCJleHAiOjE3NDk5MTQ2MjZ9.qiSgw2v89HwhH0CFbk6PamZxRYGHZUa5t2UiR8 OCpmg.

“Definitive Action Being Taken.” Tropical Sun, April 15, 1903.

“Everee Jimerson Clarke: Keeper of Pleasant City’s flame.” The Palm Beach Post, February 1, 2003. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-palm-beach-post-ejc-keeper-of-pc-fla/159780732/.

“February 19, 1904.” The Daily Miami Metropolis, February 19, 1904. https://www.newspapers.com/image/297519654/?clipping_id=159779550.

“Heavy Artillery Taken By Police.” The Palm Beach Post, December 26, 1923. https://www.newspapers.com/image/134156835/?clipping_id=174159956&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjEzNDE1NjgzNSwia WF0IjoxNzQ5ODI4MDE0LCJleHAiOjE3NDk5MTQ0MTR9.lB_GT8AQimeXrKucQ6QYrT3nDYXDDi3Af6P9rJqMiPY.

“Legal Papers Filed.” The Daily Miami Metropolis, August 4, 1905. https://www.newspapers.com/image/297525071/?clipping_id=174157952

“Makes the First Move.” Tropical Sun, February 13, 1904.

“Pleasant City Visited By Disastrous Fire.” The Palm Beach Post, November 11, 1923. https://www.newspapers.com/image/134154789/?clipping_id=174160037&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjEzNDE1NDc4OSwia WF0IjoxNzQ5ODI3ODMxLCJleHAiOjE3 NDk5MTQyMzF9.yg8LeMMgl5pXu7LfJEwqIyINIFV9dNvEEnzFF58eZmg.

“Styx Tenants Must Get Out: Thirty Days From Date.” Tropical Sun, February 17, 1904.

“We Let ‘Em Pass.” The Miami Metropolis, December 14, 1909. https://www.newspapers.com/image/297507263/?fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI5NzUwNzI2MywiaWF0IjoxNzUx NDc0NjA1LCJleHAiOjE3NTE1NjEwMDV9.d4ApdIyIHUQpguV-Em4_y48k4r1k66iBMI5OMxQr_Vc&clipping_id=159779805

“West Palm Beach.” The Daily Miami Metropolis, March 16, 1905. https://www.newspapers.com/image/297525028/?clipping_id=174157910&fcfToken=eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyJmcmVlLXZpZXctaWQiOjI5NzUyNT AyOCwiaWF0IjoxNzQ5ODI5NDAzLCJleHAiOjE3NDk5MTU4MDN9.pr_3iEsMq6SXMKDzVWd1foBcQ4efs1Hr0VgIV3XBbk8.

Photograph and Object Credits

“Charred History: Styx Burning was the End of Palm Beach’s Black Community.” Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

“Did Henry Flagler Have A Fiery Secret That He Would Never Share?” Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

Jim Crow. Hodgson. 1835-1845. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2004669584/.

Matchstick Model of the Styx. Circa 1970s. Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

Little Girl in the Styx. 1898. Photograph. Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

Payne Chapel. 1893. Photograph. Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

Payne Chapel and its founding members. 1893. Photograph. Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

“Pleasant City Family Newsletter” February 2004. Gildersleeve Collection, Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

One of Palm Beaches First Families. 1898. Photograph. Historical Society of Palm Beach County.

Robinson, Beverly J, and Beverly J Robinson. Shotgun houses, Tifton, Georgia; “Aunt” Phyllis Carter, Brookfield, Georgia. Tift County United States Georgia Brookfield Tifton, 1977. Brookfield, Georgia; Tifton, Georgia, June. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/afc1982010_17394_1/.

Royal Poinciana baseball team. 1905. Photograph. https://digitalcollections.detroitpubliclibrary.org/islandora/object/islandora%3A166930.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Palm Beach, Palm Beach County, Florida. Sanborn Map Company, De, 1908. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01361_002/.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Palm Beach, Palm Beach County, Florida. Sanborn Map Company, De, 1912. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/sanborn01361_003/.

S.W. View, Royal Poinciana, Palm Beach, Fla. Photograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. , n.d. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. . https://www.loc.gov/item/2016814322/.

The Breakers, Palm Beach, Fla. Photograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C., 1900. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016798550/.

The Currie Map of 1907, II, January 4, 1981, Box: 1. Periodical Collection, PER.00. Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach.

The Styx. Framed Photograph. 1901. Addison Mizner Collection, AM.00. Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach.

The Styx, Palm Beach. n.d. Photograph. https://cdm17191.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/asm0157/id/178.

Other:

U.S. Census Bureau, “Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics,” 2020, https://data.census.gov/table?g=040XX00US12_050XX00US12099_160XX00US1254025&d=DEC+Demographic+Profile