Introduction

A Look at the Provenance of Historic Architectural Elements

In the early twentieth century, Palm Beach had not yet become the renowned winter destination it is today. Early developers were confronted with jungles and swamps as they ventured into uncharted territory, yet they also saw the opportunity to create something entirely new and unprecedented. To create their dream estates, these prolific architects drew inspiration from their European hometowns and travels abroad. There are numerous examples of architectural pieces from old European estates finding a new home in Palm Beach. Donald Curl accredits this trend to Addison Mizner, noting that El Mirasol featured chandeliers sourced from an old Spanish castle in its living room, while El Solano utilized 300-year-old paneling and furniture in its dining room.1 Mizner, along with the architects who followed in his footsteps, aimed to evoke a sense of Old World elegance, crafting estates that seemed like they had always belonged in Palm Beach. This exhibit traces the history of these architectural elements, exploring their origins and how they came to be part of Palm Beach’s lore.

1 Donald Curl, Mizner’s Florida American Resort Architecture (New York: The Architectural History Foundation, 1984), 70.

Credits

Curated by Amanda Capote, Archives & Programming Associate, and Katie Jacob, Vice President

Archival Images & Artifacts from the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach Archives unless otherwise stated.

Addison Mizner in Palm Beach

Addison Mizner in Palm Beach

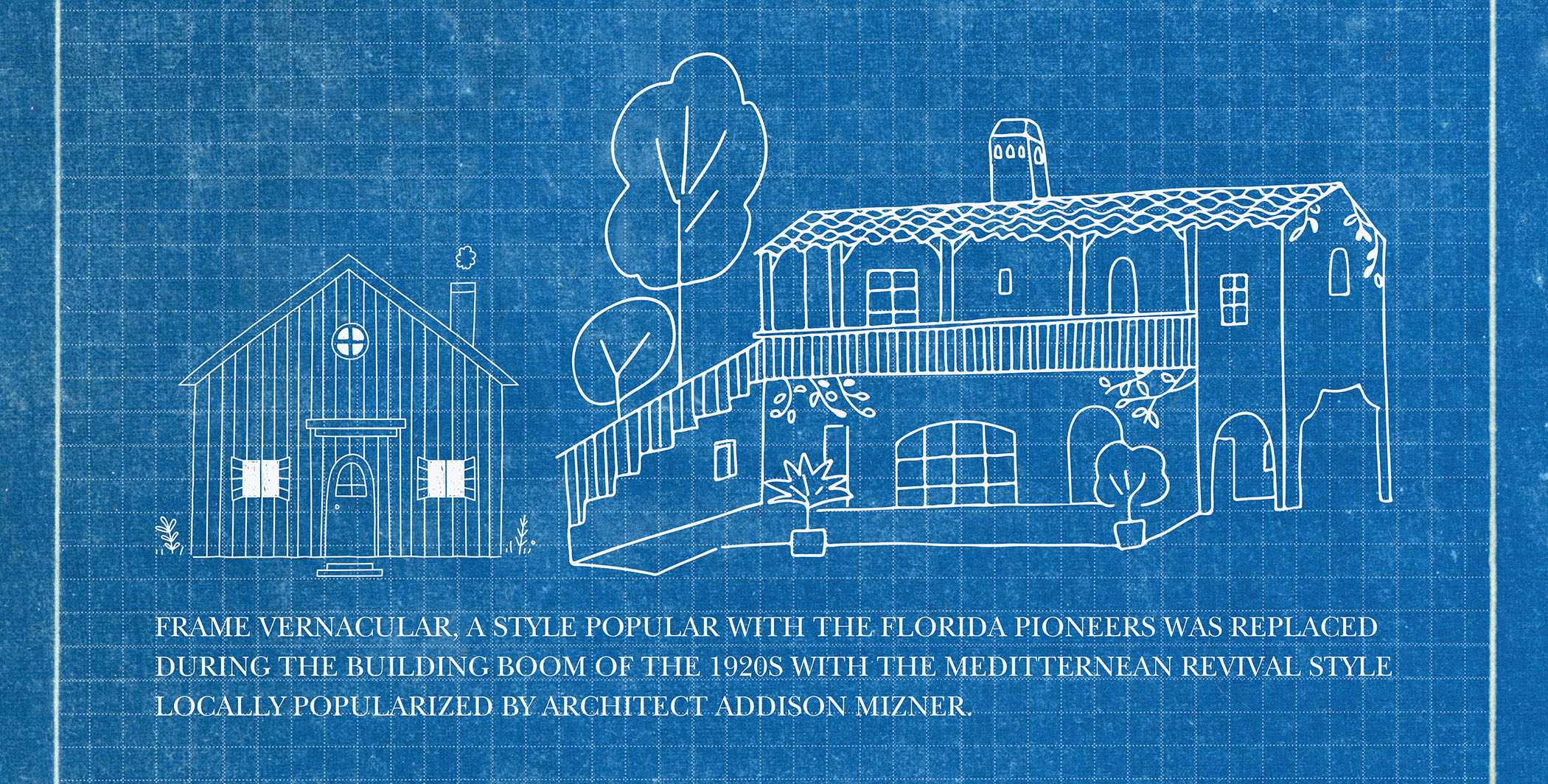

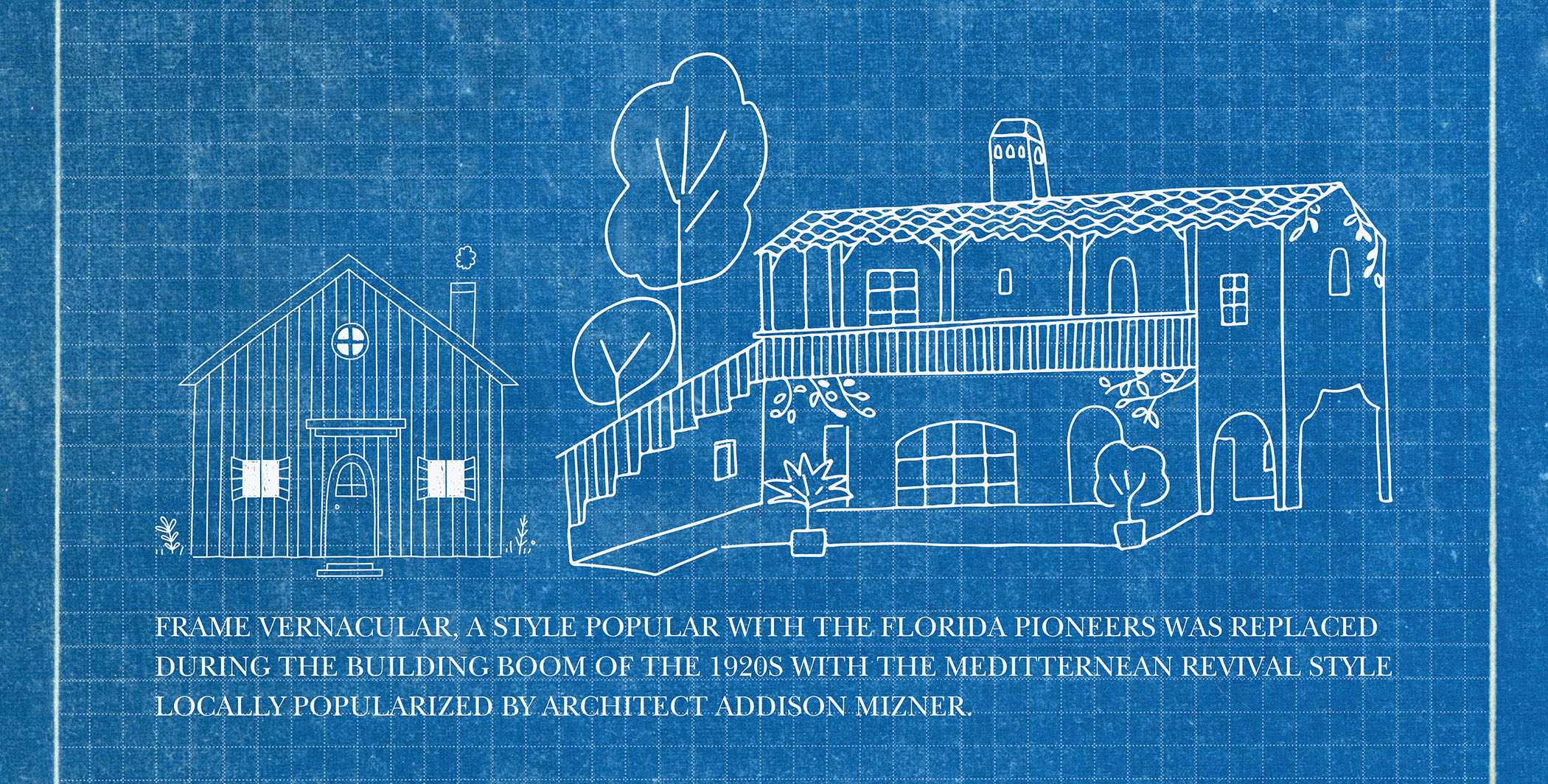

Early development in Palm Beach embraced the use of vernacular architectural styles that were popular all over the United States. It wasn’t until 1918, when Addison Mizner designed the Everglades Club, that Palm Beach would embrace the southern European architectural styles of Spain and Italy.

To complement these new Mediterranean Revival designs, Palm Beach architects embarked on buying trips across Europe, collecting antiques from estate sales and furniture shops. As construction rapidly increased during the 1920s, the need for local businesses capable of replicating authentic duplicates of these European relics became increasingly important.

Upon arrival in Palm Beach, Addison Mizner did not have access to the building materials required to create his Mediterranean Revival masterpieces. An embargo caused by World War I prevented the importation of the iconic red-barrel tiles used to roof his buildings. Mizner lamented that “all the commercial ones were stamped out and looked like painted tin when they were laid and were a horrible, lurid color, that made a roof look like the floor of a slaughterhouse.”1

Through the financial backing of Paris Singer, Mizner established Las Manos Pottery, meaning “handcrafted” in Spanish, to produce building materials for his commissions. Las Manos manufactured the much-needed red-barrel roof tiles along with other decorative tiles and wrought iron pieces such as light fixtures and ornamental gates and grilles.

1 Christina Orr, ed. Addison Mizner Architect of Dreams and Realities (Norton Gallery of Art, 1977).

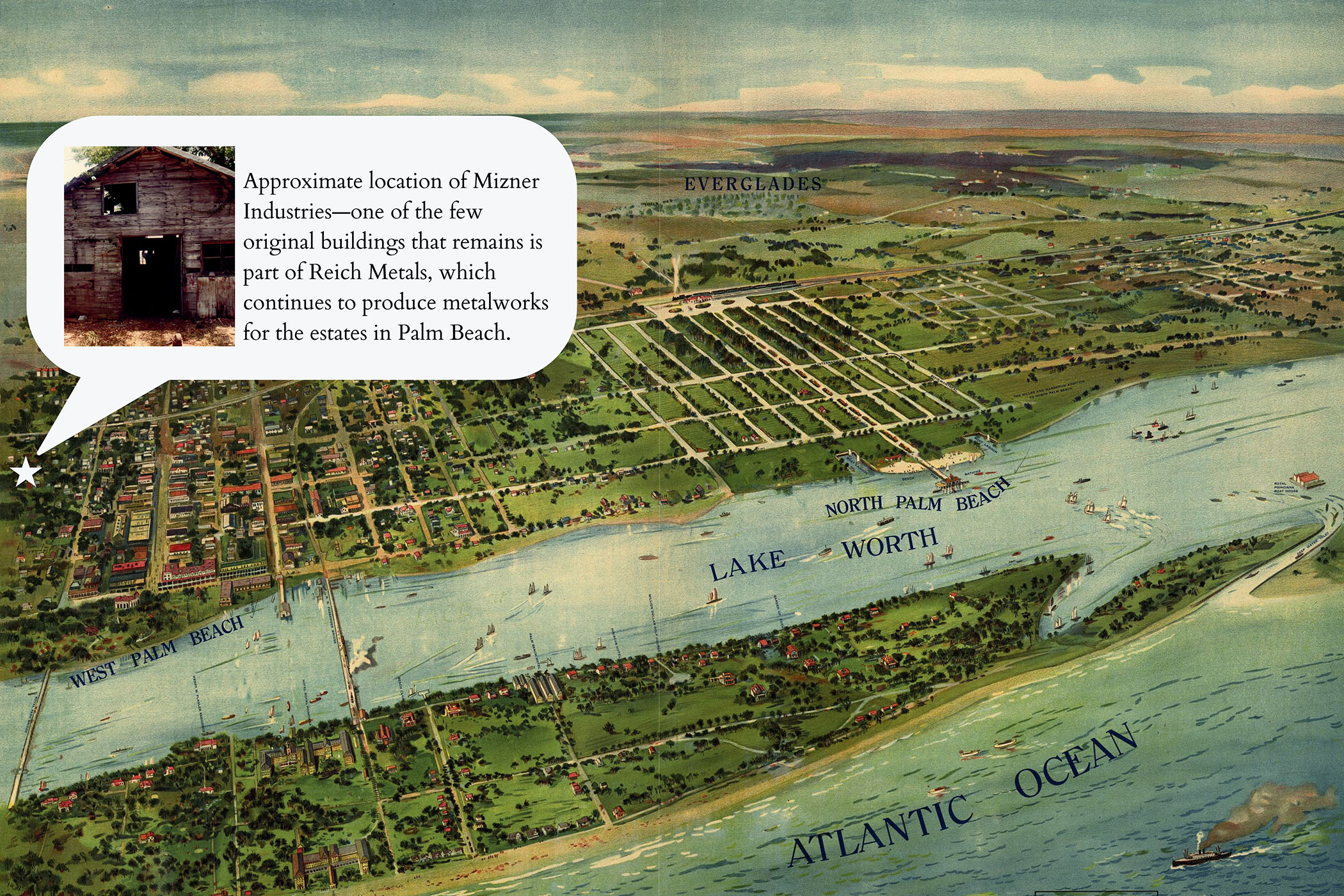

Mizner’s warehouses and factories were located where Georgia Avenue in West Palm Beach is located today. Singer originally purchased the land, but after the completion of the Everglades Club, Mizner bought out Singer and expanded the business into Mizner Industries, Inc., which included a sales office in Via Mizner. Over time, Georgia Avenue became a hub for traditional master craftsmen, including metal workers, woodworkers, stone masons, and upholsterers. The legacy of Mizner Industries is reflected in many of the businesses that exist on Georgia Avenue today, along with a strong local appreciation for preserving the building arts and traditional architecture.

Ohan Berberyan

Ohan Berberyan

Ohan Berberyan (1882-1970) was a distinguished antiquities dealer, known for his expertise in antique rugs and his significant contributions to the art and interior design communities of the early 20th century. Born in Armenia, Berberyan immigrated to the United States in 1903 and split his time between Madrid, where he sourced and curated his antiques, and his two galleries in New York and Palm Beach.

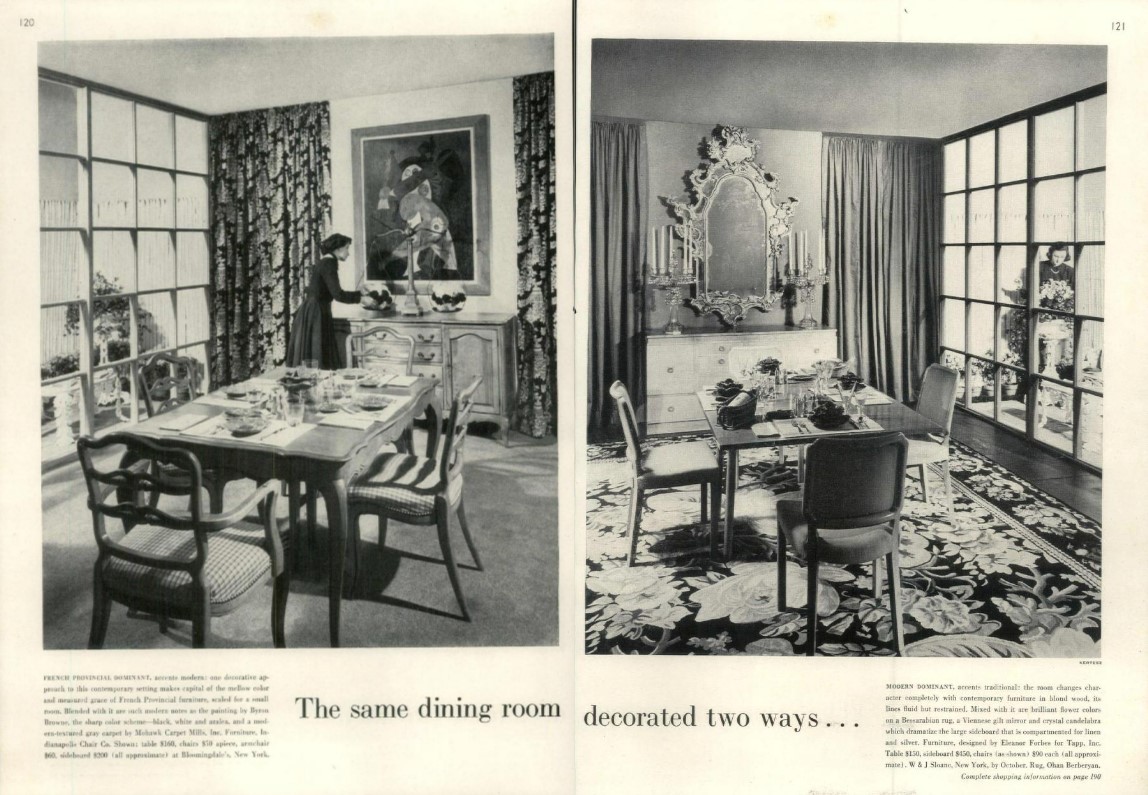

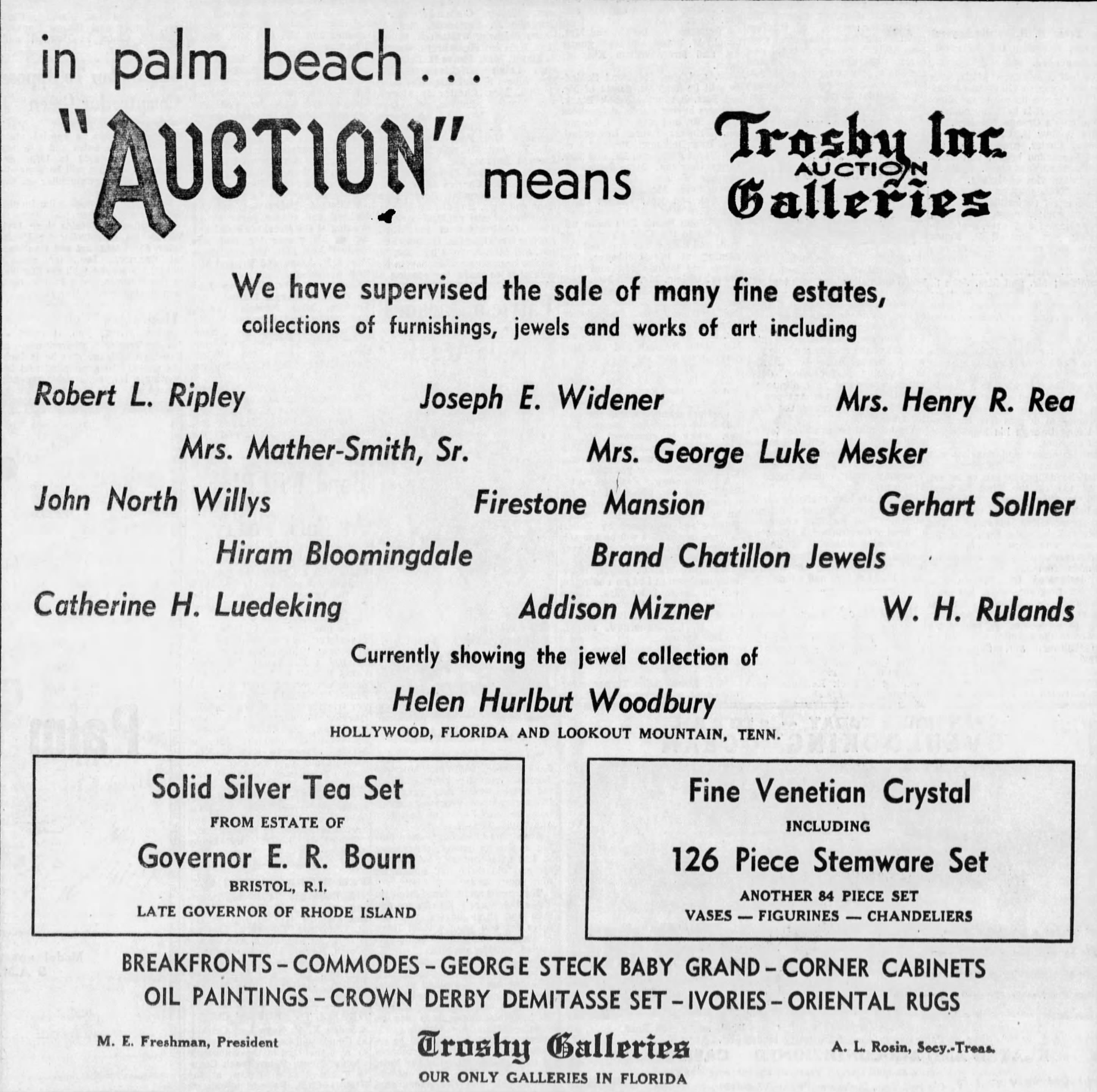

Initially, Berberyan operated his store, Spanish Art Galleries, in partnership with Addison Mizner at Via Mizner. The gallery offered authentic antiques, including paintings, sculptures, tapestries, and carpets, which were widely utilized by architects and interior designers. The gallery offered authentic antiques, including paintings, sculptures, tapestries, and carpets, which were widely utilized by architects and interior designers. Berberyan gained special notability for his antique rugs, with a 1924 American Art Association Catalog noting, “His rugs are not only acquired with a technical sense but also with a highly developed idea of design and color.”1 Berberyan’s notable commissions range from George Mesker’s Mizner-built estate La Fontana, to the James Deering estate Vila Vizcaya in Miami, and the Green Room of the White House in Washington, DC.

1 Rare and Oriental rugs from the Addison Mizner and Berberyan Collections. American Art Association, Inc., 1924. Catalog

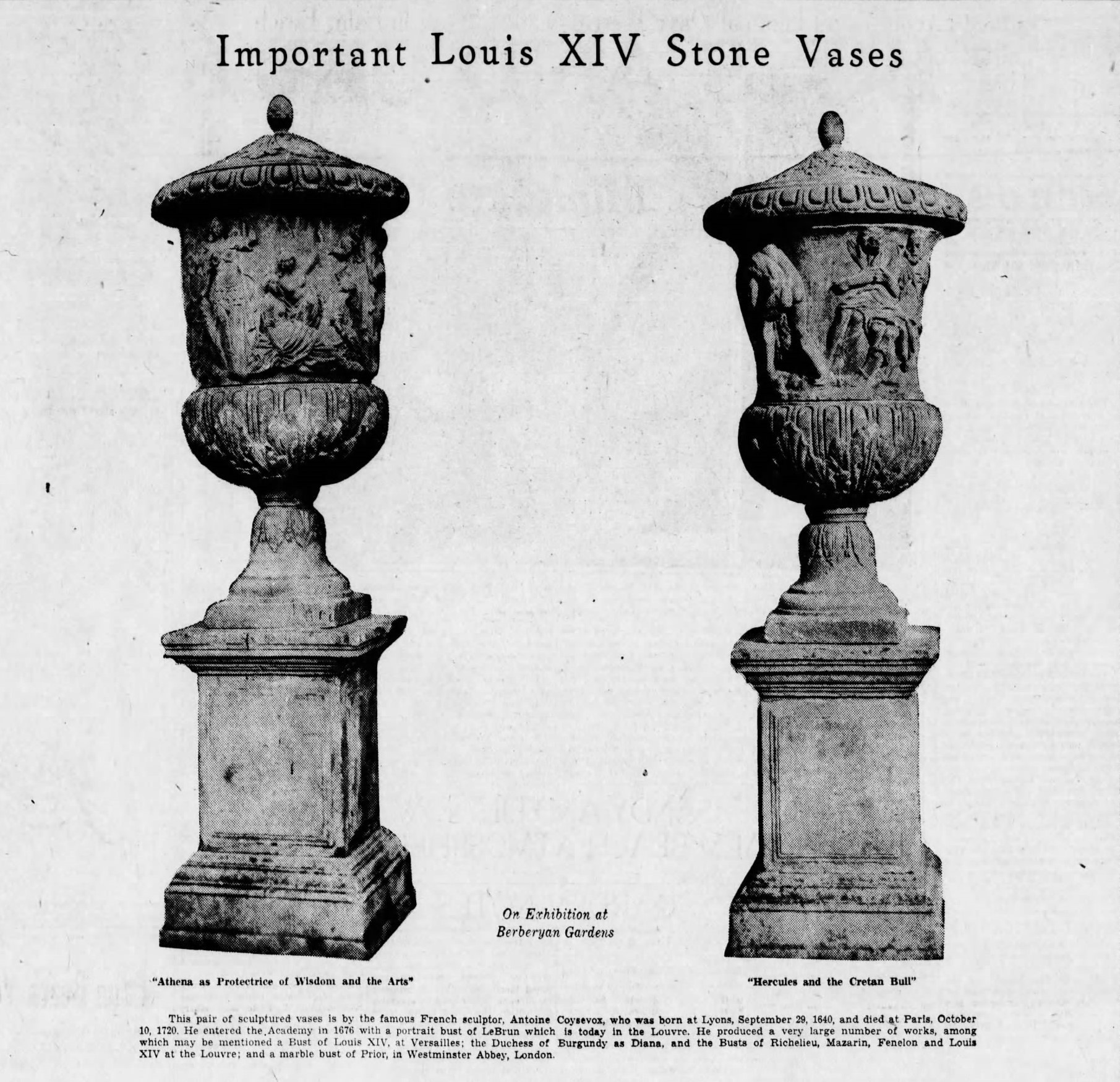

Always looking for an opportunity to showcase his wares, Berberyan created a public garden for visitors to see his classical statues and fountains for sale. Situated east of Villa Giardino, visitors would enter the garden through a grand brick arch supported by simple, Corinthian columns and experience a traditional European garden with classical statues and fountains all around. The grand entrance was once adorned with the sign “Berberyan Garden and Garden Ornaments”, and with the exception of the removal of the sign, the entrance has remained mostly unchanged since its conception.

Berberyan had a keen talent for knowing the right time, items, and methods to repurpose exceptional antiques. In a personal letter to Hon. Judge James R. Knott, Berberyan recounts the history of the lanterns adorning the Northern bridge and Colonel E.R. Bradley’s contribution.

“After the bridge was built from West Palm Beach almost up to the entrance to Bradley’s Beach Club, I suggested to him that an ornamental balustrade pylons and lamps would enhance the appearance of the approach to the club. I knew that the Duke of Devonshire’s residence was being razed to make way for The Dorchester Hotel in Mayfair, London, and that I could secure at least two very appropriate lamps. Of course, the whole thing had to go through the late Mayor Lockwood’s office, various committees, and so on, before it was approved, and by the time the thing was done it had cost the Colonel over $10,000. I do not believe that anybody now knows that Col. Bradley was responsible for this very decorative appurtenance to the Palm Beach scene.”

Villa Giardino

Villa Giardino

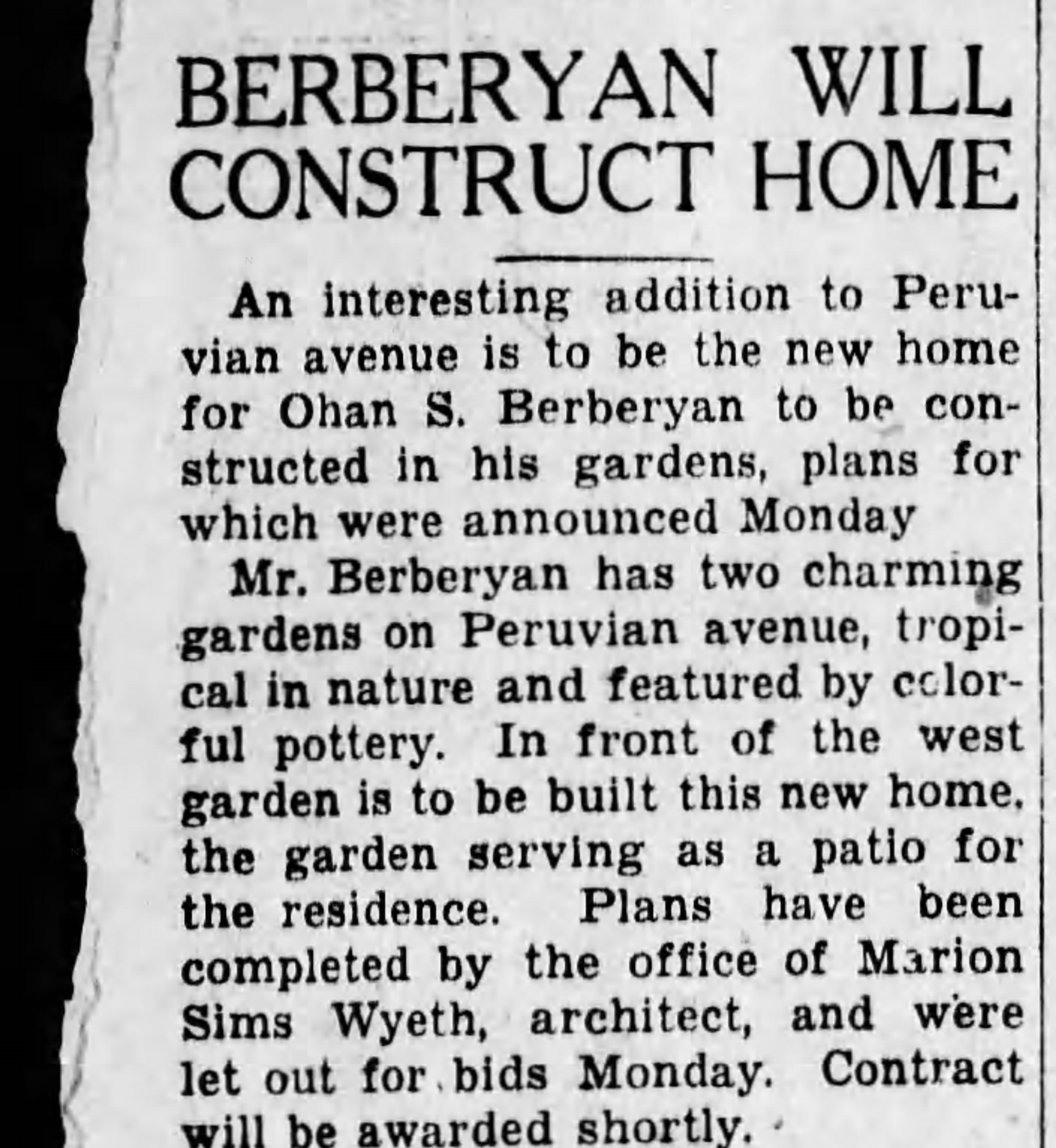

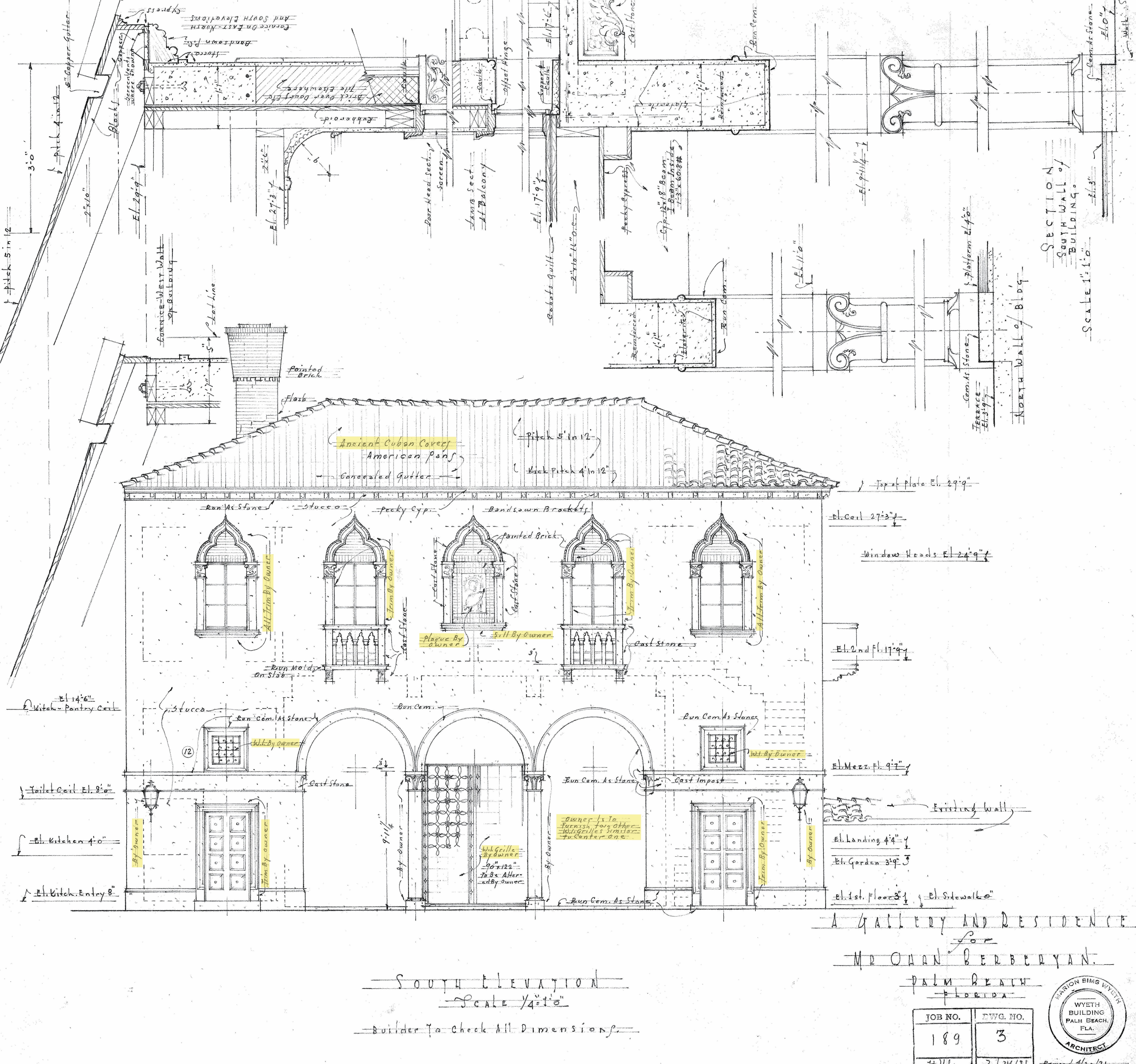

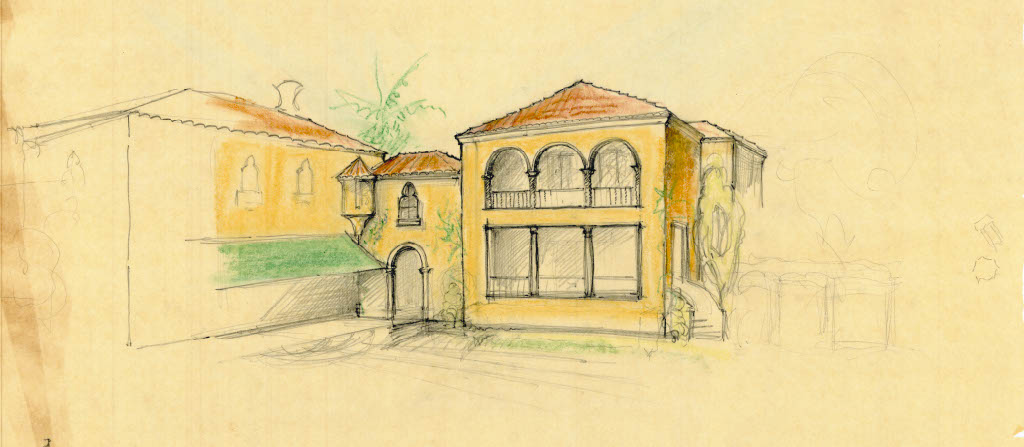

Building on his success in the market, Berberyan commissioned architect Marion Sims Wyeth (1889–1982) in 1931 to create a new store and garden, now known as Villa Giardino, located directly across from Via Mizner on Peruvian Avenue. Wyeth designed a Venetian-style building with a storefront that included an owner’s apartment on the second floor. On the architectural plans, Wyeth notes that many of the doors, windows, and grillwork will be “added by the owner,” as Berberyan wanted to highlight the fourteenth- and fifteenth century architectural elements he collected from Venice.

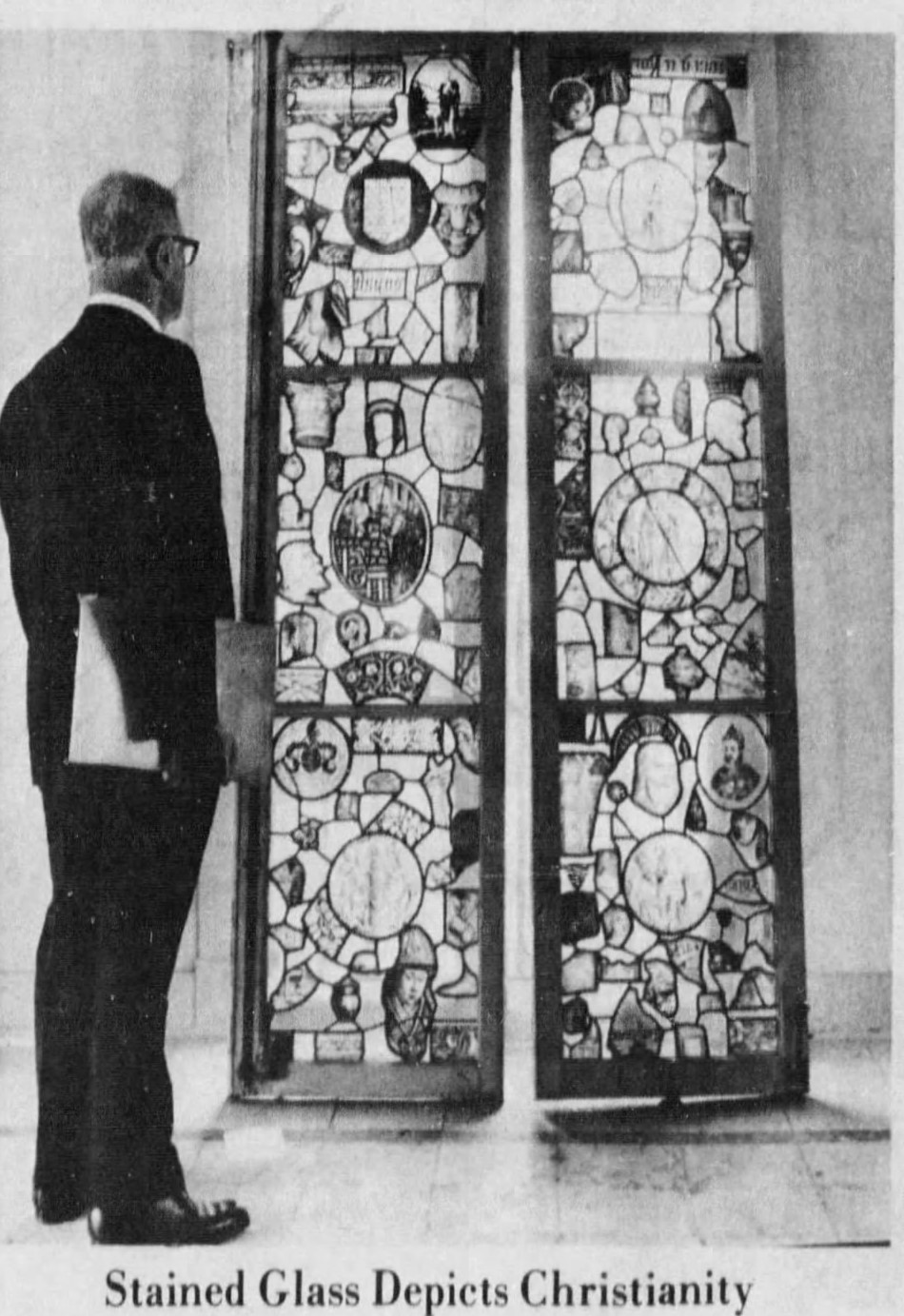

Villa Giardino elegantly combined antique architectural features with the building materials available from Mizner Industries, such as Cuban barrel clay tile roofing, to create a Venetian villa in Palm Beach. As the property changed ownership and underwent changes, new additions were incorporated, including decorative features salvaged from demolished Palm Beach estates, such as the stained glass from Mizner’s La Fontana.

Maurice Fatio

Maurice Fatio

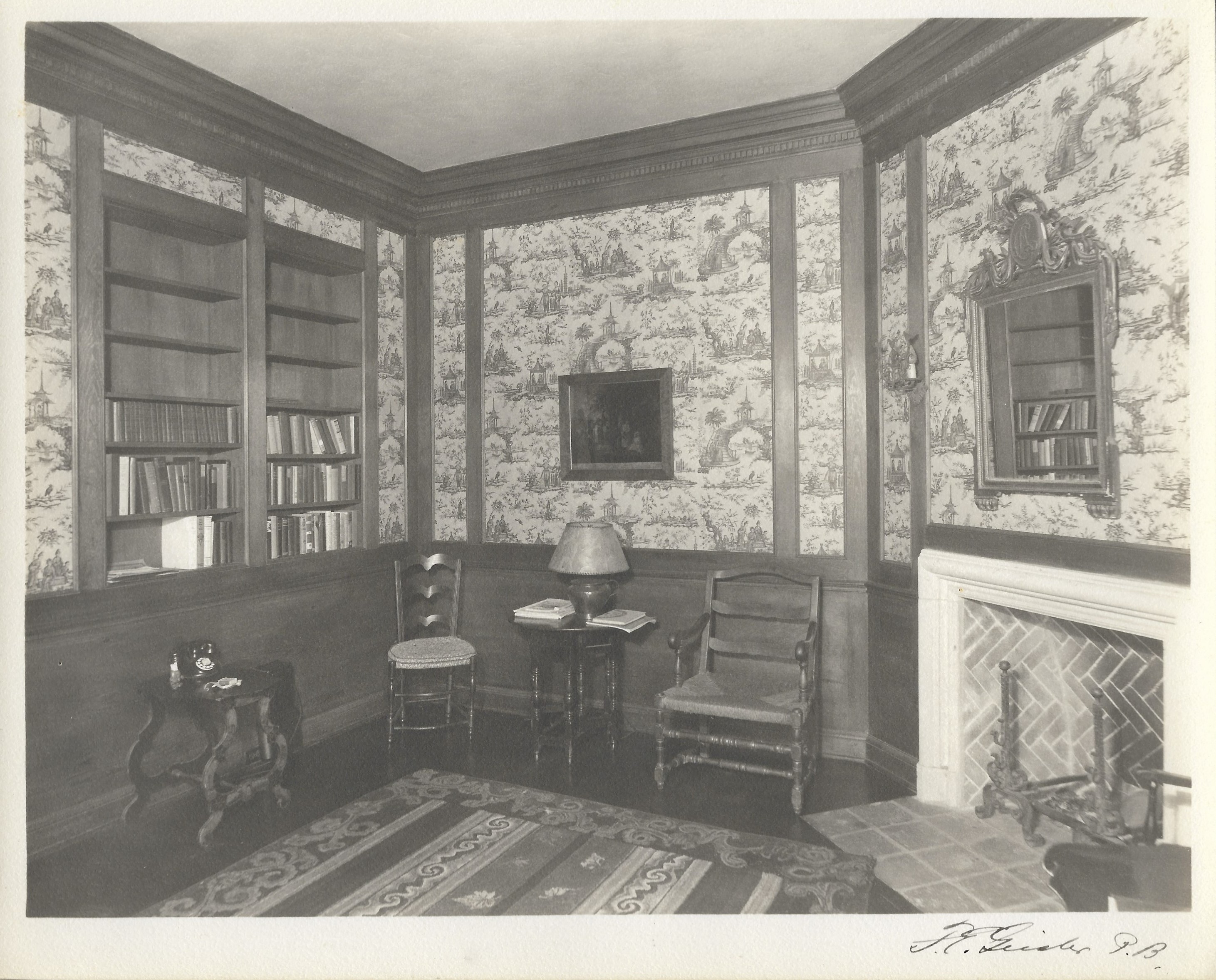

Maurice Fatio (1897–1943) followed Mizner’s technique of recreating European-style homes for his Palm Beach clients. Authenticity was important to Fatio, so he brought in craftsmen from Europe to work on his houses. The Swiss architect embraced the French Normandy style for one of his early commissions on Via del Mar for Mrs. Charles Curry Chase, Fatio’s future mother-in-law, in 1928. The ground story of the impressive two-story façade was constructed of white brick with wood trim, while the second story is half-timbered stucco. The living room is a classic Tudor-style great hall filled with tapestries, comfortable seating, and fine antiques. Fatio was known to acquire furnishings from his visits back to Europe and ship them to Palm Beach for his clients.1 The interiors featured wood paneling reminiscent of his childhood home in Switzerland.

1 Andrea Taylor. (2024, February 7) Three Women and An Architect: Maurice Fatio’s Legacy [Lecture notes]. In the lecture, Andrea stated that Maurice Fatio would “ransack” his family’s homes in Switzerland and put furniture on ships to send to his Palm Beach clients’ homes.

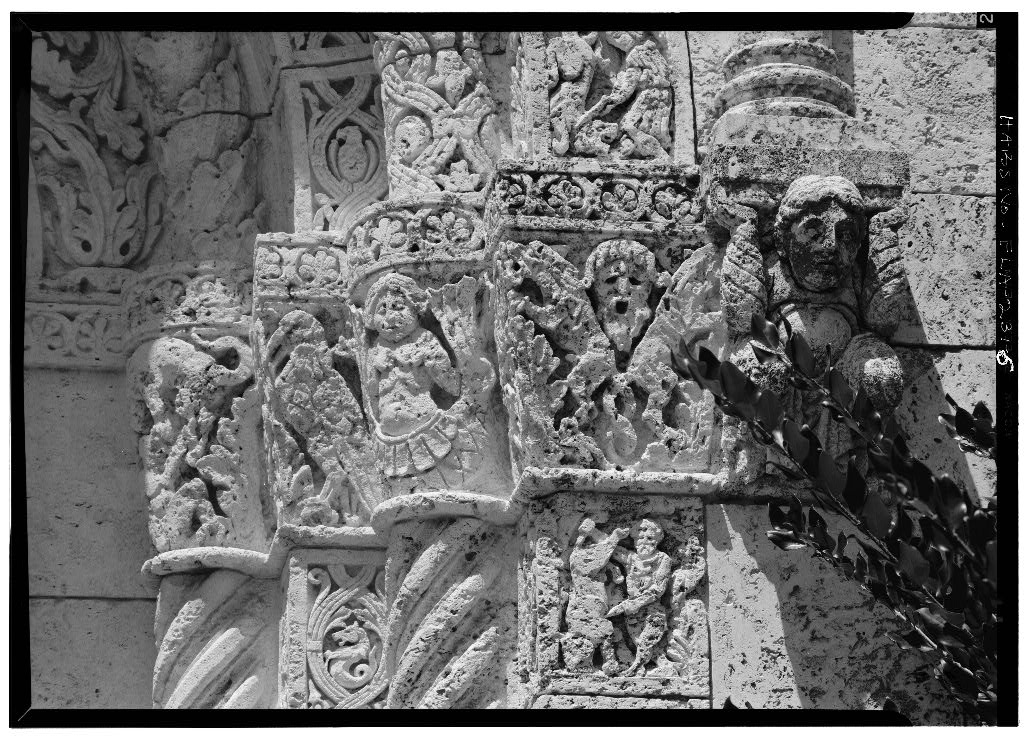

Another remarkable work by Fatio that showcases his mastery of European architectural styles is also located on Via del Mar. Commissioned in 1928 by William J. McAneeny, then-president of the Hudson Motor Car Company, this Italianate villa is celebrated for its exquisitely hand-carved doorway. Crafted by Italian stonemasons, the coquina stone is inscribed with the estate’s namesake: “Casa della Porta del Paradiso,” or “House to the Door of Paradise” in Italian. Under Fatio’s direction, the sculptors adorned the elaborate arch with mythological and Biblical scenes. Inside, the villa boasts a blend of English and Italian furnishings and antiques, including a 500-year-old English mantlepiece that frames the living room fireplace. Fatio himself regarded it as “the greatest house I have ever done.”1

1 Kim Mockler, Maurice Fatio Palm Beach Architect (New York: Acanthus Press, 2010), 45.

La Fontana and Mizner Industries

La Fontana and Mizner Industries

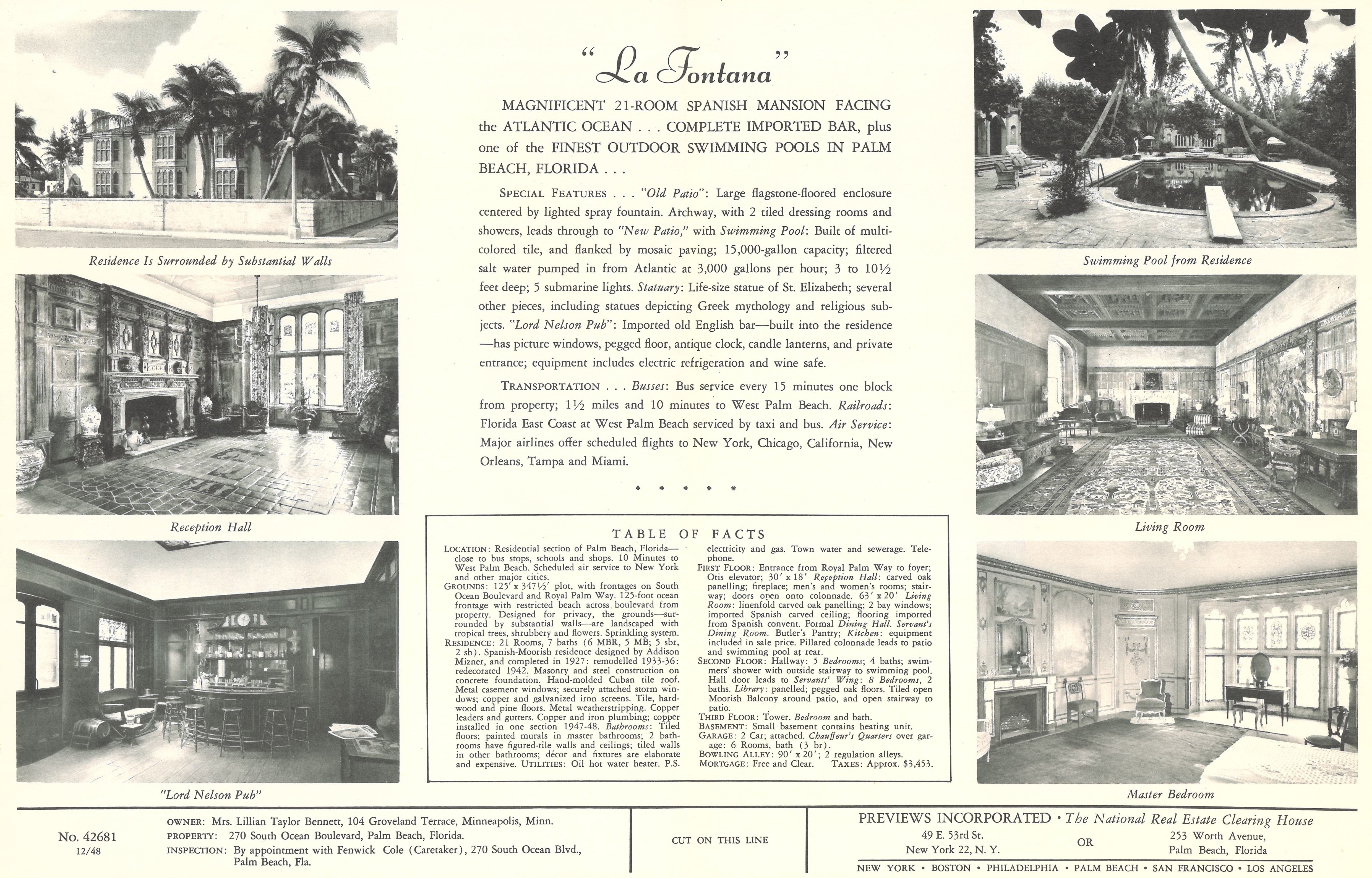

La Fontana

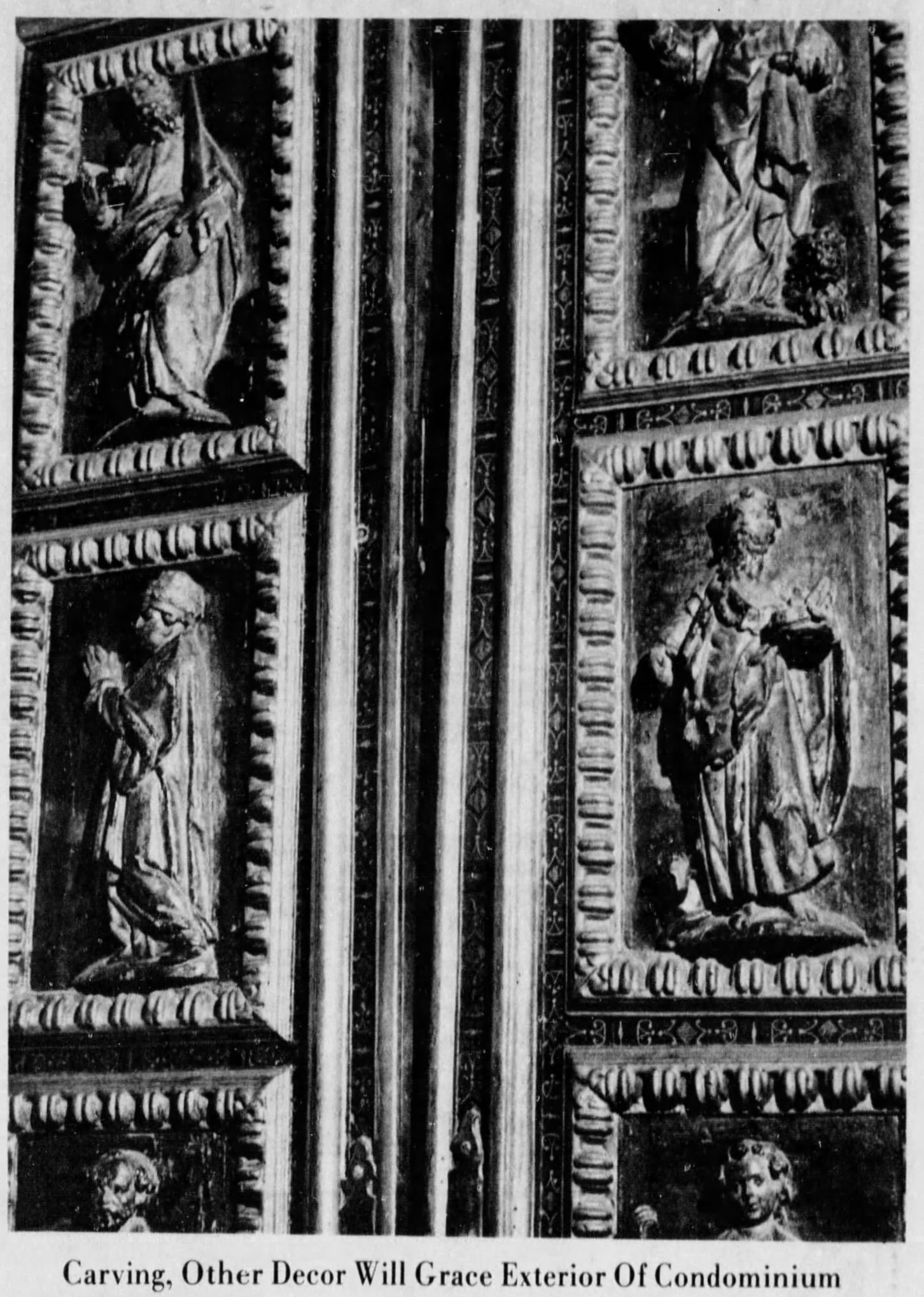

In 1923, Addison Mizner built La Fontana, a grand twenty-one-room mansion along the coast. Miner incorporated European elements inside, such as imported Spanish carved ceilings, Italian linen-fold wall paneling, and flooring sourced from a Spanish convent in the living room. The mansion’s name, La Fontana, was inspired by its centerpiece– a grand marble patio fountain adorned with life-sized cherubs playing with a fish. Unfortinately, La Fontana was demolished in 1968 to make way for the One Royal Palm Way Condos, designed by architect Howard Chilton.

However, some Mizneresque elements of La Fontana were salvaged and reused. The large marble fountain remained on the orignial site and now graces the entrance to the condos, while a portion of the mansion’s classical sculpture collection was relocated to the rooftop garden. Additionally, the linen-fold paneling was installed in the lobby of Park Place Contos on South Lake Drive, another Howard Chilton construction.

Mimicked Materials

In 1924, Mizner Industries began manufacturing doors and room paneling using a composite material called “woodlite,” which combined wood with a cohesive compound. Woodlite offered the same versatility as regular wood– it could be painted, staines, nailed, and sawn– while being more affordable to procure than authentic Spanish doors. Crafted from molds of original Spanish doors, woodlite reproductions were highly detailed and realistic. This innovation simplified the process of paneling an enture room by eliminating the need to search extensively in Europe for suitable paneling that matched the design specifications.

Like woodlite, stonework became an important division of Mizner Industries, wtih a focus on quarry keystone, a limestone consisting primarily of brain coral, which was transported by railroad from a Mizner-owned quarry on Islamorada in the Florida Keys. This stone was mainly used for outdoor terraces and stairs.

To cut down on construction time and costs, Mizner Industries also developed artifical, or cast, stone. Due to the scarcity of native Florida stone, they experimented with creating poured stone, a mixture believed to contain coquina shell, lime, and a cement compound. Molds crafted from Spanish examples were used to produce the stone in the factory, comlpete with realistic mars and fractures. Under Mizner’s instruction, workers deliberately damaged the finished products to achieve an antique appearance.