Introduction

Marion Sims Wyeth (1889–1982) was born in New York City and studied at Princeton University and the École des Beaux Arts. In 1919, he founded his architectural firm in Palm Beach with partner Frederic Rhinelander King. Wyeth was among a group of architects considered the “Big Five,” along with John Volk, Addison Mizner, Maurice Fatio, and Howard Major, who defined Palm Beach style in the early twentieth century. He was commissioned to design over 700 projects in Palm Beach and beyond during his fifty-four-year practice. Wyeth explored many architectural styles that adhered to his belief of creating “quiet, subdued, and rational buildings.”

Credits

Curated by Marie Penny and Katie Jacob.

Archival Images from the Marion Sims Wyeth Collection at the Preservation Foundation of Palm Beach Archives, unless otherwise noted.

The exhibition is generously underwritten by Kyle Blackmon Team.

Golfview Road

Golfview Road

A neighborhood for the “right kind of young marrieds” was the motivation behind the Golf View Road Development company. Designed in 1921 by Marion Sims Wyeth, Marjorie Merriweather Post and Edward Francis Hutton’s home Hogarcito stands at the terminus of the private street. Wanting to further develop the street, Hutton enlisted Wyeth to create a series of speculative homes located on every other lot. Wyeth became the architect and developer with funding from Hutton, who chose to remain a silent partner.

Because the homes were developed speculatively, Wyeth had full creative control of the design process. Utilizing the Mediterranean Revival style, Wyeth embarked on creating a new neighborhood in Palm Beach according to his ideal vision. The result was a cohesively designed street of five houses on the north side of Golfview Road completed within two years.

In 1924, Clarence Geist commissioned Wyeth to build opposite of Hogarcito. The Spanish Baroque style home known as La Claridad provides a dramatic foil to Hogarcito’s Spanish Revival simplicity. The most ornate house on the street, La Claridad showcases Wyeth’s authentic hand when applying the historic Spanish architectural details to the home.

Wyeth in Europe

Wyeth in Europe

Upon completing his undergraduate studies at Princeton in 1910, Wyeth traveled to Paris, France, to attend the world-renowned architecture school at the École des Beaux Arts. In 1912 Wyeth was admitted to the École through the rigorous entrance competition and studied under Henri Delgane, one of the architects of the Grand Palais des Champs Élysées. The École was an influential institution that educated other notable architects such as Charles McKim of McKim, Mead & White, and Carrère and Hastings—for whom Wyeth later worked as a draftsman. Wyeth’s education in classical proportions and geometry prepared him for the many great works he would design.

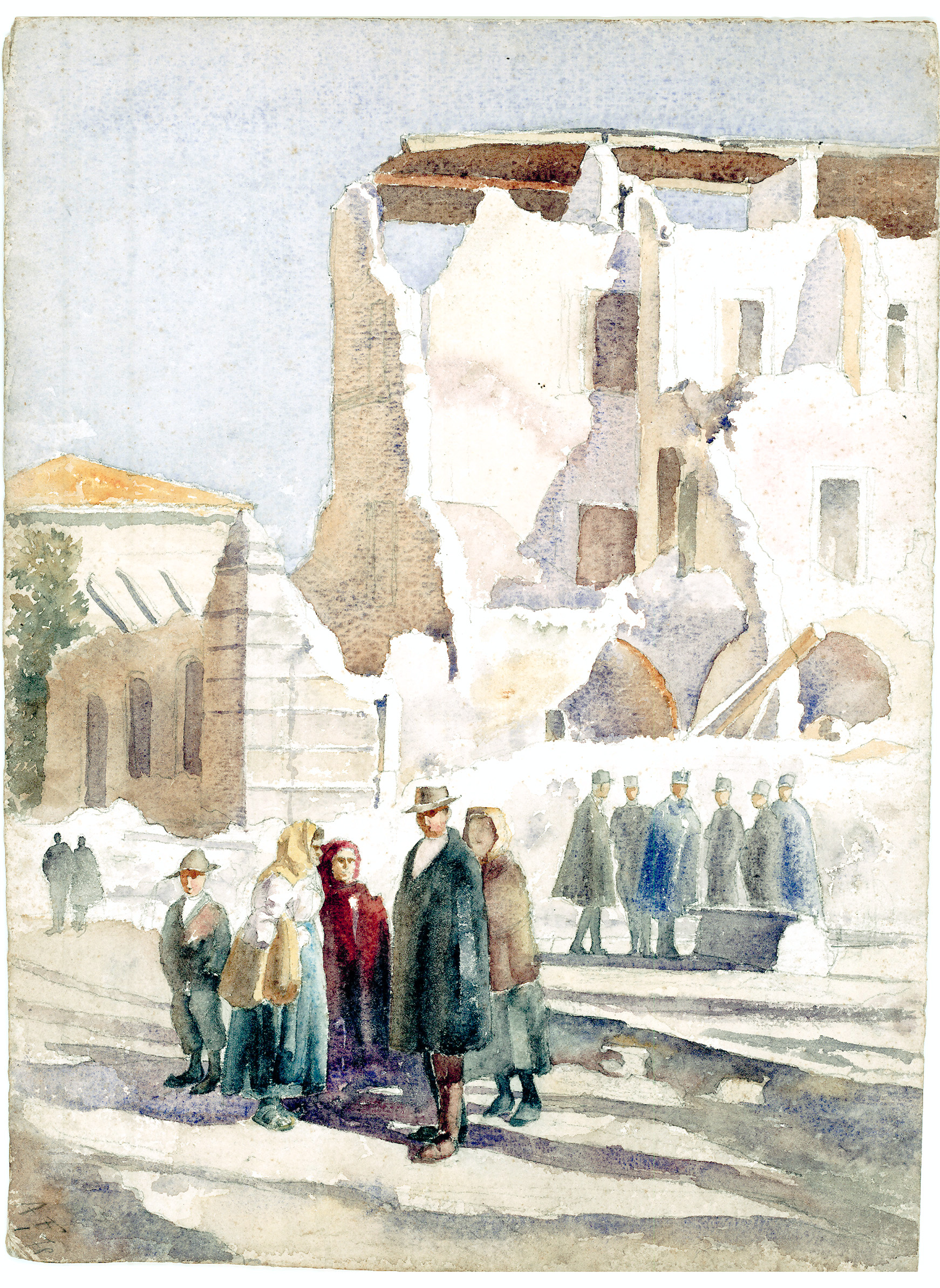

In 1914 Wyeth traveled to Rome where he served as private secretary to Thomas Nelson Page, the American ambassador in Italy. The position allowed Wyeth to study classical architecture in the field. During his time in Europe, he also visited his aunt, who had a villa in Rapallo near Genoa, Italy, where he painted watercolor studies of the countryside. These studies are a direct connection to the architect as a young man and artist, and they demonstrate how his travels influenced his later designs.

Art: Through Wyeth’s Eyes

Southwood

Southwood

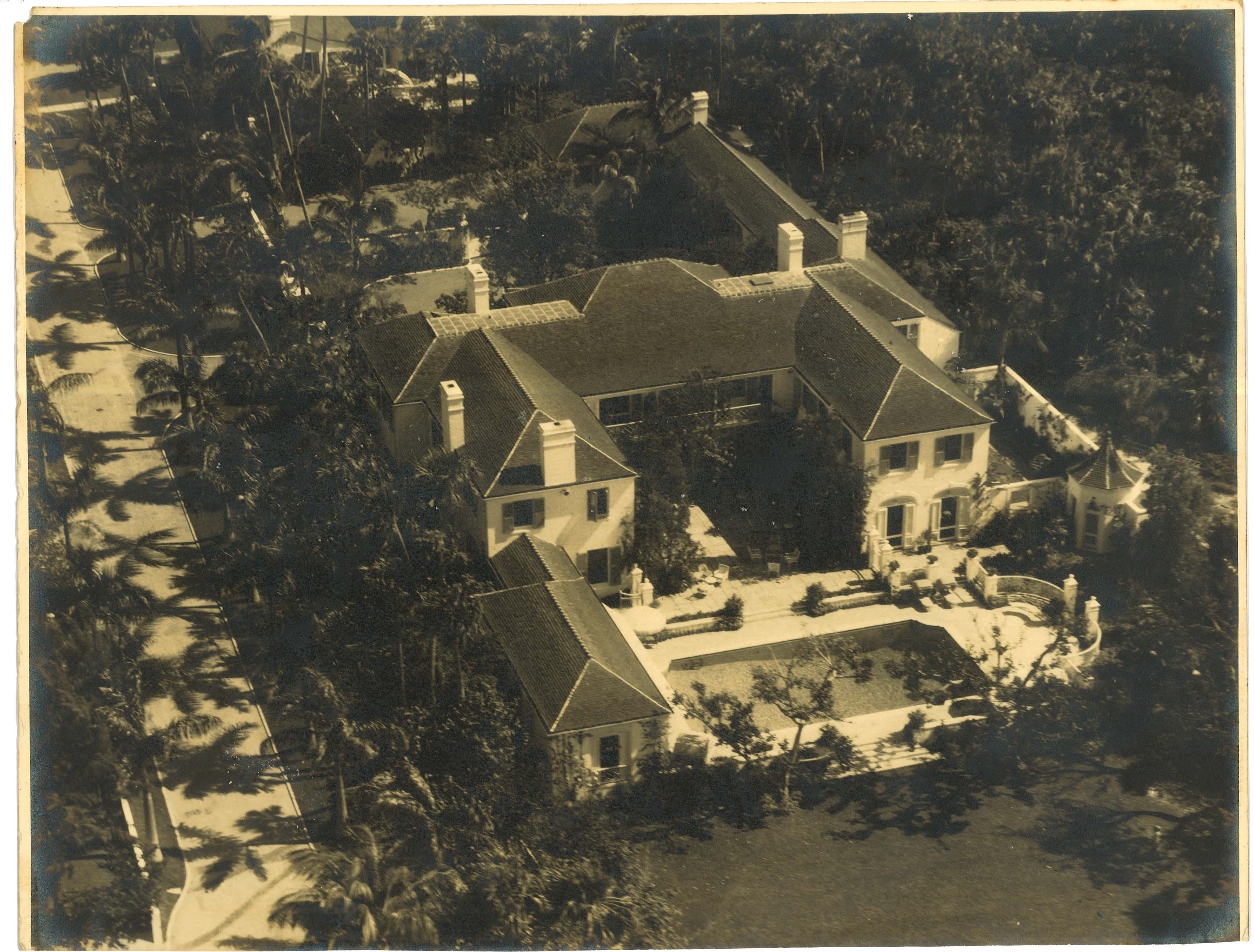

The spacious lakefront estate known as Southwood was designed by Marion Sims Wyeth in 1934. The spare-no-expense estate was commissioned by Dr. John A. Vietor and his wife, Eleanor Woodward Vietor, a Jell-O heiress, at the cost $190,000—or about $2.4 million adjusted for inflation. Wyeth incorporated Monterey and Southern Colonial details, which was a departure from the prevailing Mediterranean Revival style that was popular prior to the Great Depression.

The U-shaped layout of the home provides not only expansive views of the lakefront but also allows the outdoors to come inside. Wyeth is even quoted as saying, “Climate is important here. I try to make the outside part of the house.”

Shangri La

Shangri La

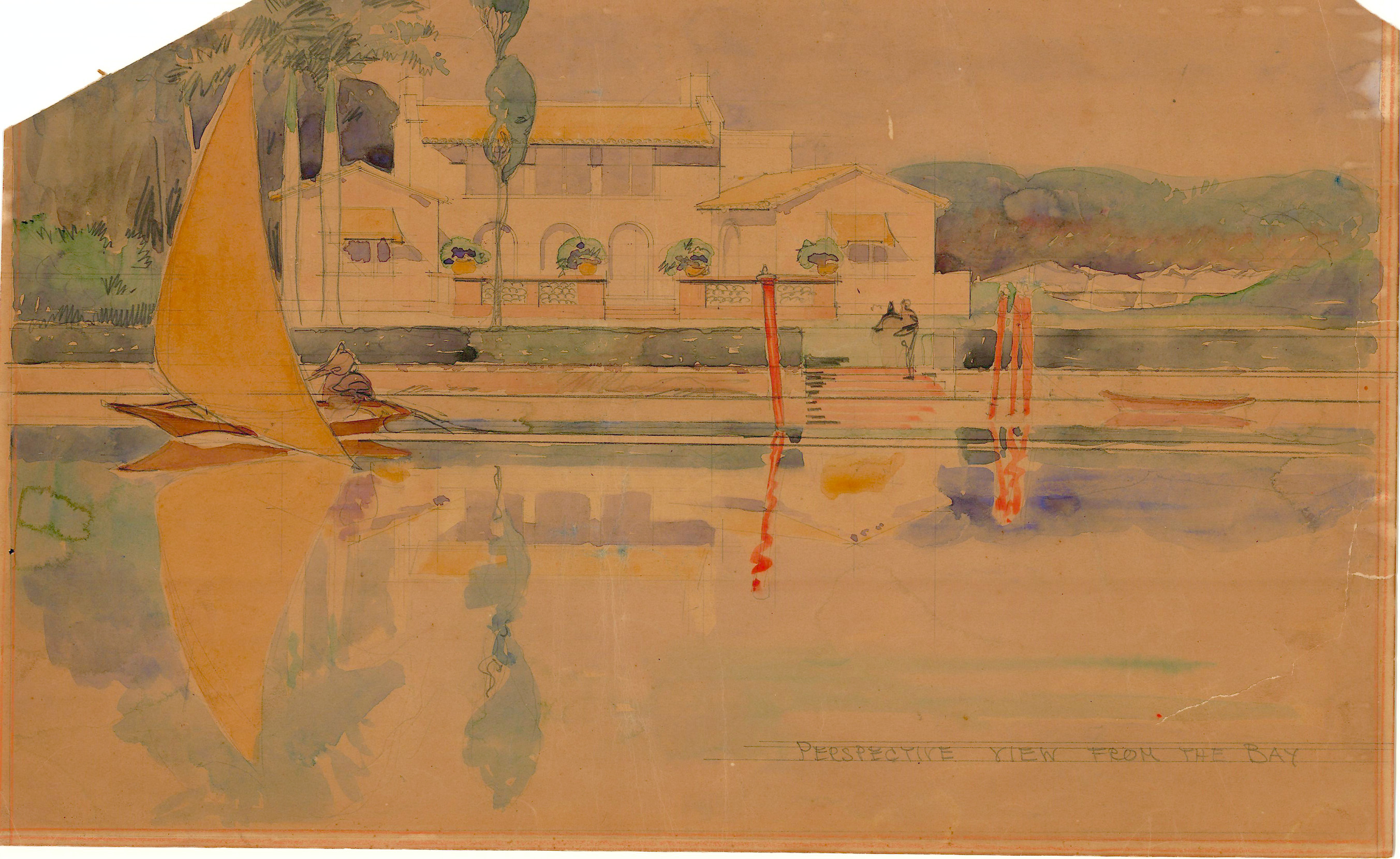

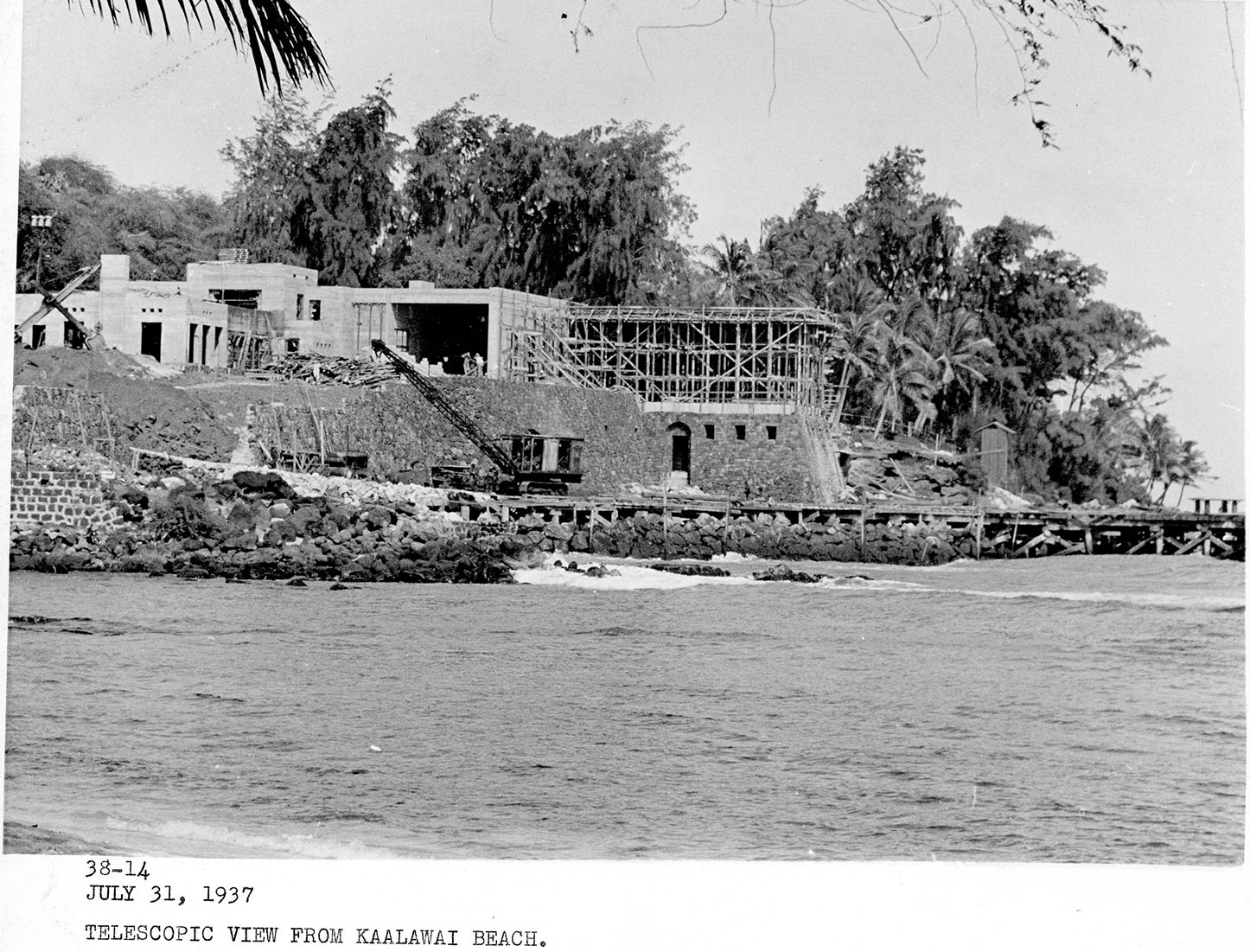

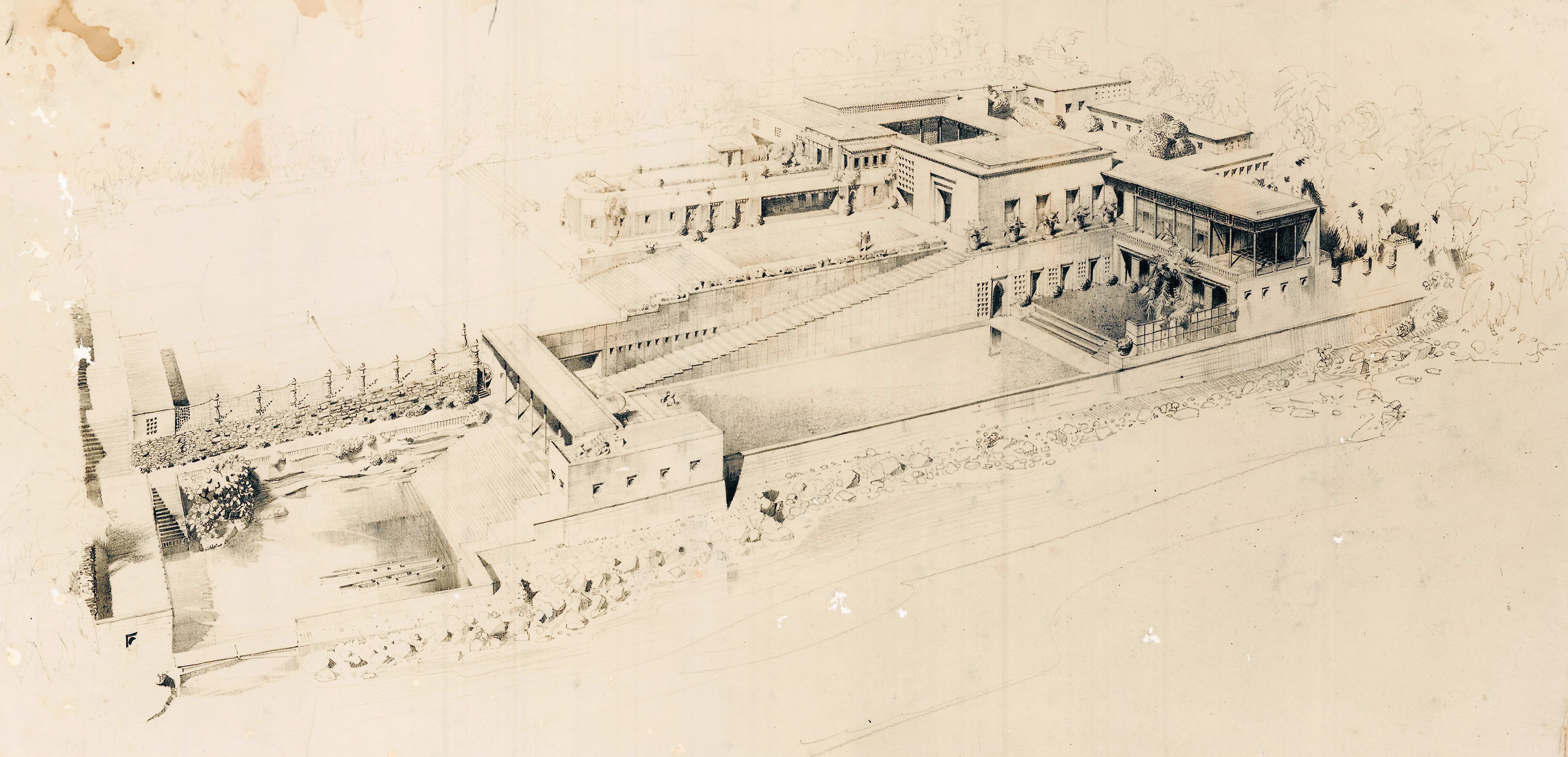

Evoking the fabled city, the Shangri La designed by Marion Sims Wyeth for newlyweds Doris Duke and James Cromwell merges Wyeth’s distinctive architectural style and Duke’s love of Islamic art. Originally, Duke was inspired to recreate the Taj Mahal in Palm Beach, but once they stopped in Honolulu, Hawaii, their plans changed. Shangri La would be the first home that Doris Duke commissioned to be built.

Her familiarity with Wyeth’s work led her to choose him to design her new estate. Its dramatic location on the island of Oahu provided a picturesque backdrop for Wyeth’s design. Wyeth utilized a subdued courtyard design, allowing Duke to showcase her ever-expanding Islamic art collection. Early descriptions of the house stated there would only be three bedrooms and one guest room, though in actuality the final space is approximately fourteen thousand square feet of connected indoor and outdoor spaces.

Norton Museum

Norton Museum of Art

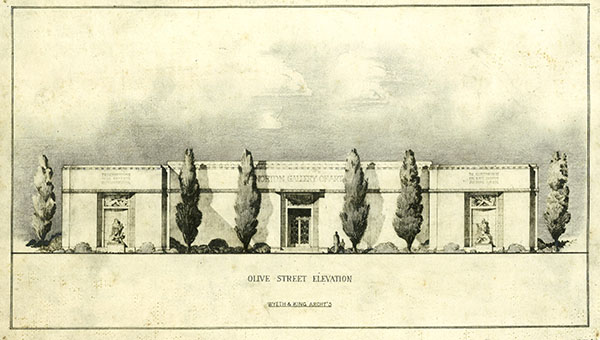

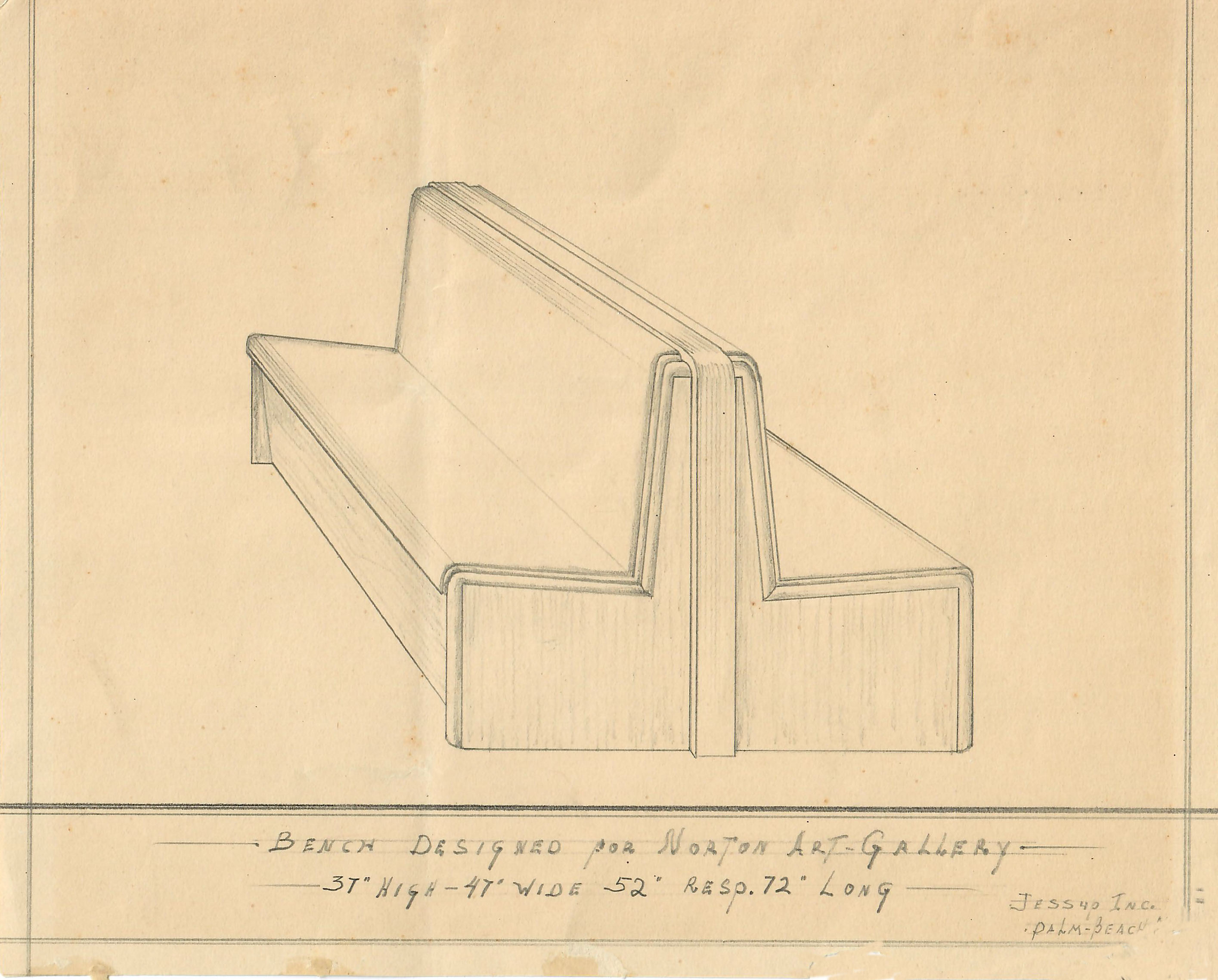

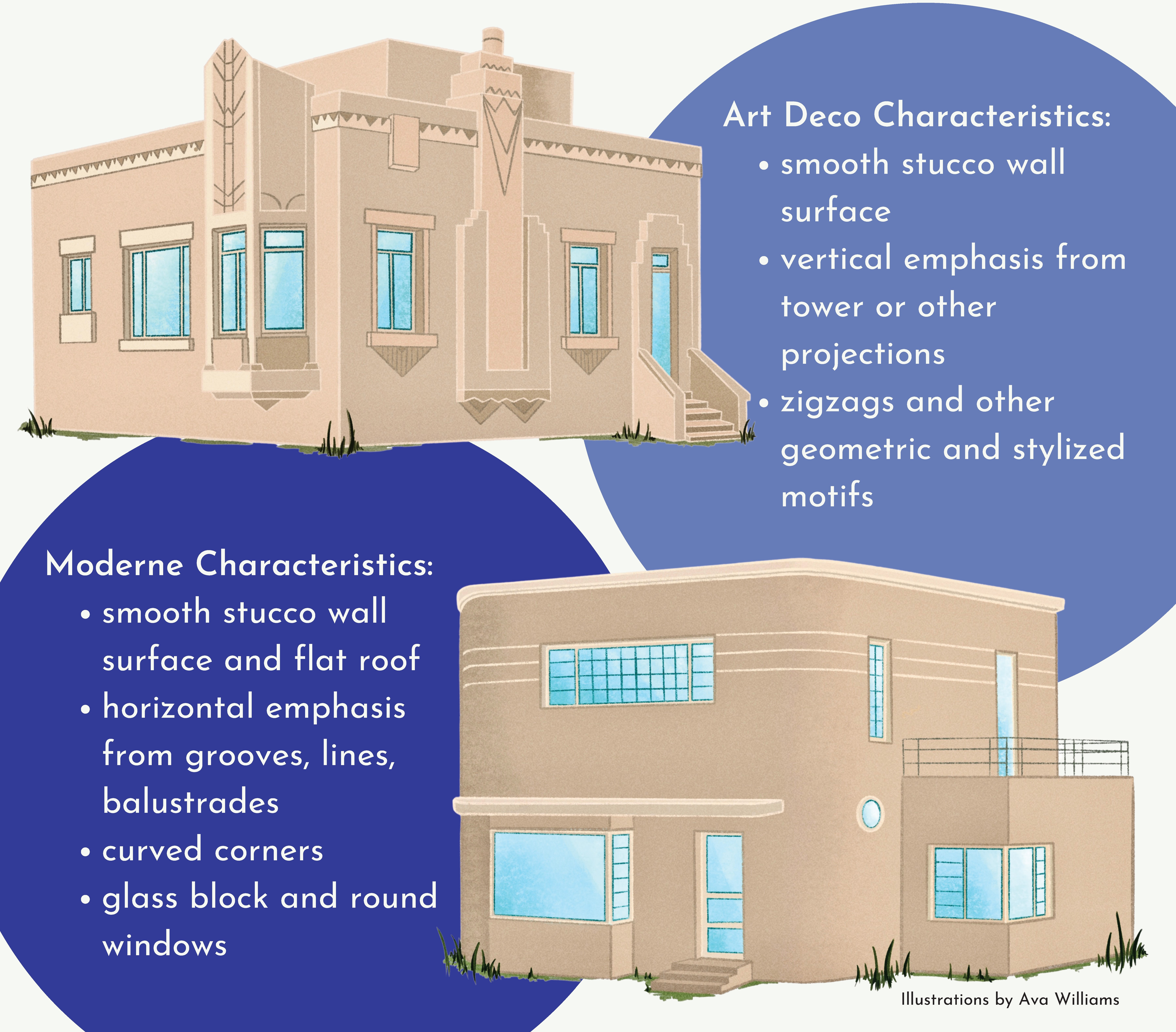

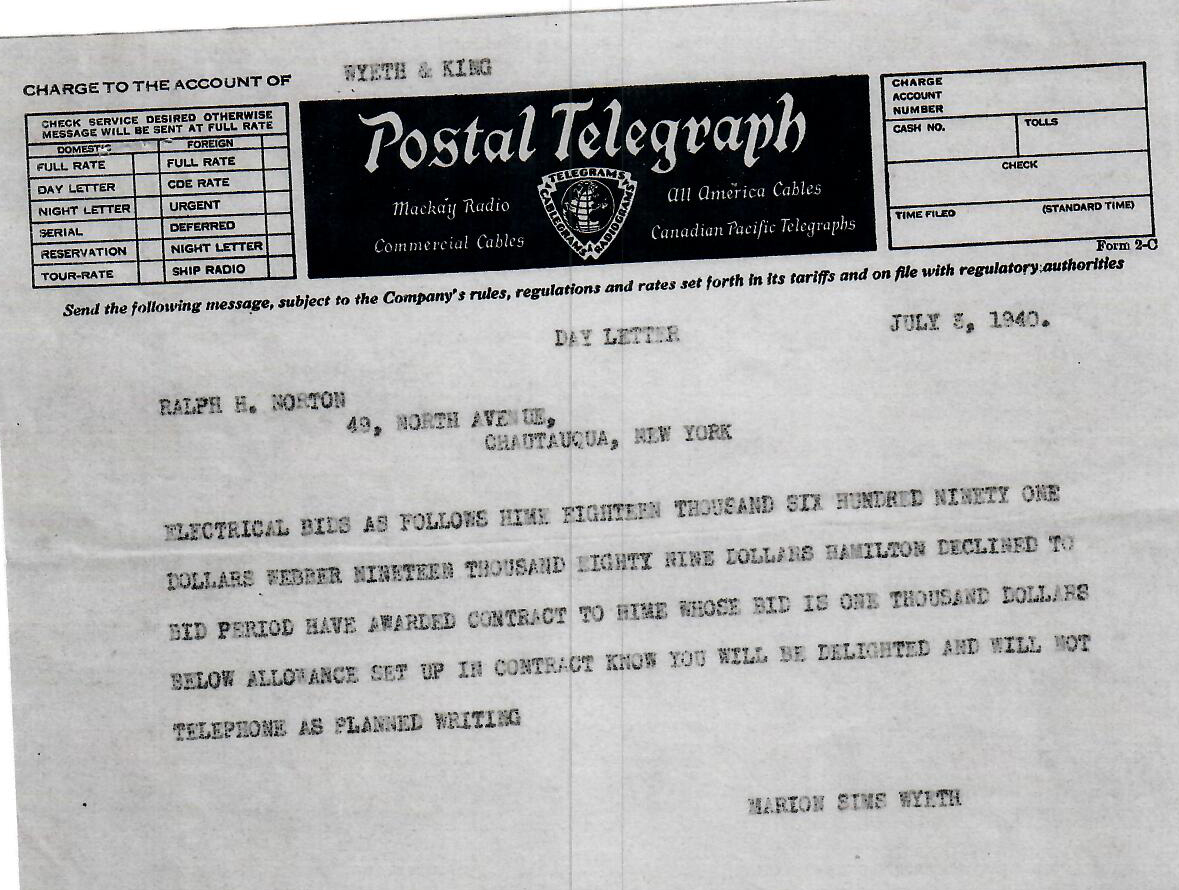

Marion Sims Wyeth first worked with Ralph and Elizabeth Norton in 1935, when he transformed their Mediterranean Revival house on Barcelona Road in West Palm Beach into a Monterey style home (now the Ann Norton Sculpture Gardens). A few years later in 1940, Norton commissioned Wyeth & King to design the Norton Gallery and School of Art (now known as the Norton Museum of Art). The Gallery and School was the first of its kind in South Florida, and Wyeth worked closely with Norton to create a building to house his art collection and educate the community. It was designed in the modern version of the Beaux Arts style: Art Deco. Wyeth’s design remains an integral part of the museum, which underwent a major expansion in 2019 by Foster + Partners.

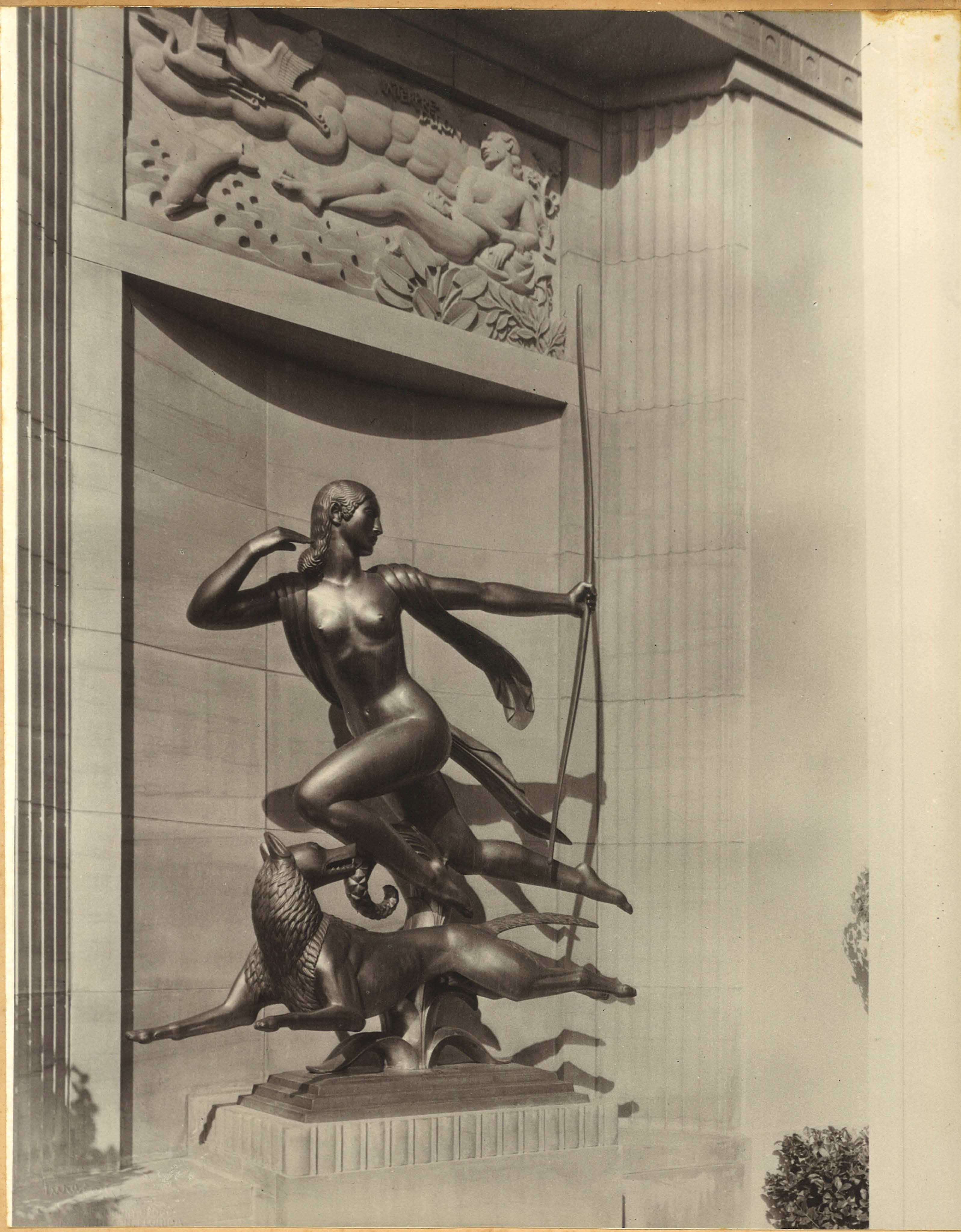

Sculpture Study

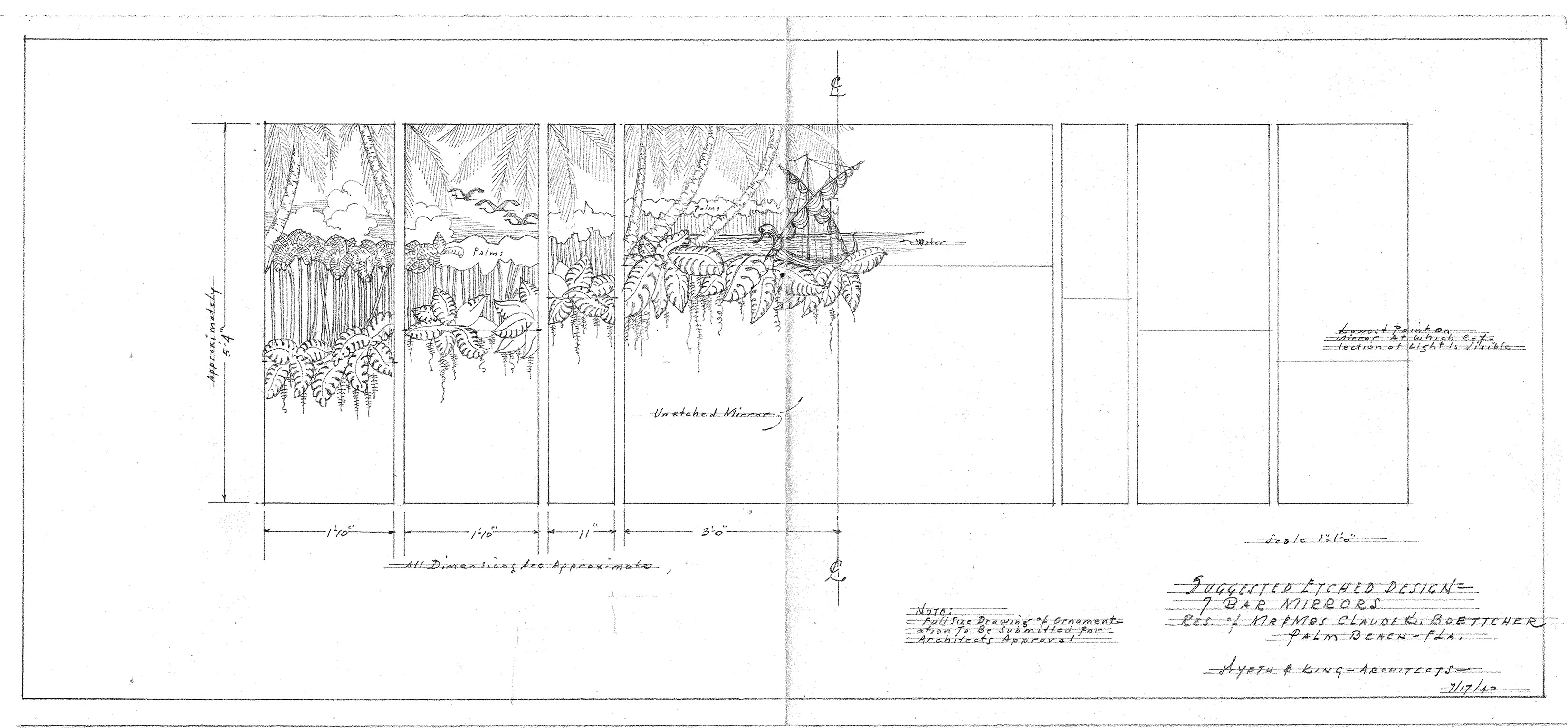

The original entrance of the building faced South Olive Avenue with a tripartite, symmetrical façade. Wyeth recommended Paul Manship, one of the leading Art Deco sculptors in the United States, to design the sculptures that would reside in the niches on either side of the entrance. William Johnson, an architect who worked for Wyeth and later became a partner, was tasked with creating studies of the mythological figures Diana and Actaeon to determine what scale they would be cast in. Wyeth and Manship also explored different concepts for the bas-reliefs that would be placed above the statues. In this study of Diana, an alternate bas-relief representing sculpture as an artform was used. Note that “Inscription here” was a placeholder for the passage from Henry Austin Dobson’s Ars Victrix: “All passes. Art alone enduring / stays to us. The bust outlasts / the throne. The coin Tiberius.”